Dinosaurs

Creatures from another age

241 files

-

Avimimus by Moondawg

By Guest

Avimimus was a small dinosaur, standing about 45 centimeters (2.5 ft) tall at the hips and

a length of 1.5 m (5 ft). The skull was relatively small compared to the body, though the

brain and eyes were relatively large. The size of the bones which surrounded the brain and

were dedicated to protecting it are large. This is also consistent with the hypothesis

that Avimimus had a proportionally large brain.

As in the related Oviraptoridae and Caenagnathidae, the jaws of Avimimus formed a

parrot-like beak, and lacked teeth. However, a series of toothlike projections along the

tip of the premaxilla would have given the beak a serrated edge. The toothless beak of

Avimimus suggests that it may have been an herbivore or omnivore. Kurzanov himself,

however, believed that Avimimus was an insectivore.

The foramen magnum, the hole allowing the spinal cord to connect with the brain, was

proportionally large in Avimimus. The occipital condyle, however, was small, further

suggestive of the skull's relative lightness.The neck itself was long and slender, and is

composed of vertebrae are much more elongate than in other oviraptorosaurs. Unlike

oviraptorids and caenagnathids, the back vertebrae lack openings for air sacs, suggesting

that Avimimus is more primitive than these animals.

The forelimbs were relatively short. The bones of the hand were fused together, as in

modern birds, and a ridge on the ulna (lower arm bone) was interpreted as an attachment

point for feathers by Kurzanov.Kurzanov, in 1987, also reported the presence of quill

knobs, and while Chiappe confirmed the presence of bumps on the ulna, their function

remained unclear. Kurzanov was so convinced they were attachment points for feathers that

he concluded that Avimimus may have been capable of weak flight. This interpretation has

not seen wide support among paleontologists, however.

The ilium was almost horizontally oriented, resulting in exceptionally broad hips. Little

is known of the tail but the hip suggests that the tail was long. The legs were extremely

long and slender, suggesting that Avimimus was a highly specialized runner. The

proportions of the leg bones add further weight to the idea of Avimimus was quick on its

feet. The animal's shins were long in comparison with its thighs, a trait common among

cursorial animals. It also had three-toed feet with narrow pointed claws.

Its remains were discovered in the Djadokta Formation by Russian paleontologists, and

officially described by Dr. Sergei Kurzanov in 1981. The type species is A. portentosus.

Because no tail was found with the original find, Dr. Kurzanov mistakenly concluded that

Avimimus lacked a tail in life. However, subsequent Avimimus finds containing caudal

vertebrae have confirmed the presence of a tail.

In 1991, Sankar Chatterjee erected the Order Avimimiformes to include Avimimus, though

this group is not used by most paleontologists today as it includes only a single species.

283 downloads

Updated

-

Nemegtosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

It was named after the Nemegt Basin in the Gobi Desert, where the remains were found. It may have had a long, sloping head and, like most sauropods, had peg-shaped teeth.

The type species, Nemegtosaurus mongoliensis, was first described by Nowinski in 1971. A second species, N. pachi, was described by Dong in 1977, but is a nomen dubium.

174 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Arrhinoceratops by Moondawg

By Guest

Arrhinoceratops belonged to the Ceratopsinae (previously known as Chasmosaurinae) within the Ceratopsia (the name is Ancient Greek for "horned face"), a group of herbivorous dinosaurs with parrot-like beaks which thrived in North America and Asia during the Cretaceous Period, which ended roughly 65 million years ago. It appears to be closely related to Torosaurus.

Since this dinosaur is known only from its skull, scientists know little about its over-all anatomy. The skull features a broad neck frill with two oval shaped openings.

Its brow horns were moderately long, but its nose horn was shorter and blunter than most Ceratopsians

Its body is assumed to be typical of the Ceratopsians, and based on the skull it is estimated to be 6 m (20 ft) long when fully grown.

Arrhinoceratops, like all Ceratopsians, was a herbivore. During the Cretaceous, flowering plants were "geographically limited on the landscape", and so it is likely that this dinosaur fed on the predominant plants of the era: ferns, cycads and conifers. It would have used its sharp Ceratopsian beak to bite off the leaves or needles.

359 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Daspletosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Daspletosaurus is closely related to the much larger and more recent Tyrannosaurus. Like most known tyrannosaurids, it was a multi-ton bipedal predator equipped with dozens of large, sharp teeth. Daspletosaurus had the small forelimbs typical of tyrannosaurids, although they were proportionately longer than in other genera.

As an apex predator, Daspletosaurus was at the top of the food chain, probably preying on large dinosaurs like the ceratopsid Centrosaurus and the hadrosaur Hypacrosaurus. In some areas, Daspletosaurus coexisted with another tyrannosaurid, Gorgosaurus, though there is some evidence of niche differentiation between the two. While Daspletosaurus fossils are rarer than other tyrannosaurids, the available specimens allow some analysis of the biology of these animals, including social behavior, diet and life history.

While very large by the standard of modern predators, Daspletosaurus was not the largest tyrannosaurid. Adults could reach a length of 8–9 meters (26–30 ft) from snout to tail. Mass estimates have centered around 2.5 tonnes (2.75 short tons)but have ranged between 1.8 tonnes (2 tons)and 3.8 tonnes (4.1 tons).

Life restoration of Daspletosaurus. Daspletosaurus had a massive skull that could reach more than 1 meter (3.3 ft) in length. The bones were heavily constructed and some, including the nasal bones on top of the snout, were fused for strength. Large fenestrae (openings) in the skull reduced its weight. An adult Daspletosaurus was armed with about six dozen teeth that were very long but oval in cross section rather than blade-like. Unlike its other teeth, those in the premaxilla at the end of the upper jaw had a D-shaped cross section, an example of heterodonty always seen in tyrannosaurids. Unique skull features included the rough outer surface of the maxilla (upper jaw bone) and the pronounced crests around the eyes on the lacrimal, postorbital, and jugal bones. The orbit (eye socket) was a tall oval, somewhere in between the circular shape seen in Gorgosaurus and the 'keyhole' shape of Tyrannosaurus.

Daspletosaurus shared the same body form as other tyrannosaurids, with a short, S-shaped neck supporting the massive skull. It walked on its two thick hindlimbs, which ended in four-toed feet, although the first digit (the hallux) did not contact the ground. In contrast, the forelimbs were extremely small and bore only two digits, although Daspletosaurus had the longest forelimbs in proportion to body size of any tyrannosaurid. A long, heavy tail served as a counterweight to the head and torso, with the center of gravity over the hips.

242 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Alvarezsaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

The Alvarezsauridae are an enigmatic family of small, long-legged running dinosaurs. Although originally thought to represent the earliest known flightless birds, a consensus of recent work suggests that they are primitive members of the Maniraptoriformes. Other work found them to be the sister group to the Ornithomimosauria. Alvarezsaurs are highly specialized. They bear tiny but stoutly proportioned forelimbs with compact birdlike hands and their skeleton suggests they had massive breast and arm muscles, possibly adapted for digging or tearing. They have tubular snouts, elongate jaws, and minute teeth. They may have been adapted to prey on colonial insects such as termites. Alvarezsaurids range from 0.5.2 m (20-80 inches) in length, although some possible members may have been substantially larger, including the European Heptasteornis (also called Elopteryx) that may have reached 2.5 m (8 ft).

At least one species of Alvarezsaurid, Shuvuuia deserti, has down-like, feathery, integumental structures that are preserved in the fossil. Schweitzer et al. (1999) subjected these filaments to microscopic, morphological, mass spectrometric, and immunohistochemical studies and found that they consisted of beta Keratin, which is the primary protein in feathers.

Alvarezsaurus, and thus Alvarezsaurinae, Alvaresauridae, and Alvarezsauria are named for the historian Don Gregorio Alvarez, not the more familiar physicist Luis Alvarez, who proposed that the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event was caused by an impact event.

The type species is A. calvoi. It was bipedal, had a long tail and its leg structure suggests that it was a fast runner. It may have been insectivorous and was basal to better-known members of its family, such as Mononykus and Shuvuuia. It has been alternately classified with both non-avian theropod dinosaurs and early birds

260 downloads

Updated

-

Anchiceratops by Moondawg

By Guest

American paleontologist Barnum Brown named Anchiceratops in 1914, as he believed Anchiceratops was a transitional form closely related to both Monoclonius and Triceratops and intermediate between them.

There is one valid species known today (A. ornatus), whose name refers to the ornate margin of its frill. A second species was named A. longirostris by Charles M. Sternberg in 1929, but this species is widely considered a junior synonym of A. ornatus today.

The first remains of Anchiceratops were discovered along the Red Deer River in the Canadian province of Alberta in 1912 by an expedition led by Barnum Brown.The holotype is the back half of a skull, including the long frill,and several other partial skulls were found at the same time, which are now stored in the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. A complete skull was discovered by C.M. Sternberg in 1924, and described as A. longirostris five years later. Another specimen, collected by Sternberg in 1925, lacks the skull but is otherwise the most complete skeleton known from any ceratopsid, preserving a complete spinal column down to the last tail vertebra. Sternberg's material is now housed in the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa. Other material has been found since, including one or two bonebed deposits in Alberta, but very little Anchiceratops material has been described.

Anchiceratops ornatus.Anchiceratops frills are very distinctive. Rectangular in shape, the frill is edged by large epoccipitals (triangular bony projections), and has smaller fenestrae (window-like openings) than those seen in other chasmosaurines like Pentaceratops and Torosaurus.Another characteristic feature is the pair of bony knobs located on either side of the midline, towards the end of the frill.

Most Anchiceratops fossils have been discovered in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, which belongs to the early part of the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous Period (74-70 million years ago). Frill fragments found in the early Maastrichtian Almond Formation of Wyoming in the United States resemble Anchiceratops (Farke, 2004). However, pieces of a frill have been found from two localities in the older Dinosaur Park Formation (late Campanian, 78-74 million years ago) with the characteristic pattern of points seen in Anchiceratops frills. This may represent an early record of A. ornatus or possibly a second, related species (Langston, 1959).

453 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Dromaeosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

The first known Dromaeosaurus remains were first discovered by paleontologist Barnum Brown during a 1914 expedition to the Judith River Formation on behalf of the American Museum of Natural history. The area where these bones were collected is now part of Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta, Canada. The find consisted of a partial skull 9 inches in length and some foot bones. Several other bones, and dozens of isolated teeth, are also known from subsequent discoveries in Alberta and the western United States.[1]

Several species of Dromaeosaurus have been described, but Dromaeosaurus albertensis is the most complete specimen. Additionally, it is apparent that this genus is even rarer than other small theropods, although it was one of the first small theropods described based on reasonably good cranial material.

In 1969 similarities in anatomy between Dromaeosaurus and its relative Deinonychus were first observed. Based on the sickle-claws and commonalities in the skull, a new family, the dromaeosauridae was erected to house these two genera.[1] Since then, many new relatives of Dromaeosaurus have been found.

Dromaeosaurus differs from most other Dromaeosauridae in having a short, massive skull, a deep mandible, and robust teeth. In these respects Dromaeosaurus resembled the tyrannosaurs. The teeth tend to be more heavily worn than those of its relative Saurornitholestes, suggesting that its jaws were used for crushing and tearing rather than simply slicing through flesh.

It is possible that Dromaeosaurus was more of a scavenger than other small theropods, or it may be that Dromaeosaurus relied more heavily on its jaws to dispatch its prey. It was probably better suited to tackling large prey than the more lightly built Saurornitholestes.

The relationships of Dromaeosaurus are unclear. Although its rugged build gives it a primitive appearance, it was actually a very specialized animal. It is usually given its own subfamily, the Dromaeosaurinae; this group is thought to include Utahraptor, Achillobator, Adasaurus and perhaps Deinonychus.

However, the relationships of dromaeosaurs are still in a state of flux. "Dromaeosaurus Morphotype A" is the designation given to a series of unusual, ridged dromaeosaur teeth from Alberta. These teeth probably do not belong to Dromaeosaurus, although it is unclear from what animal they do come.

201 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Pelecanimimus by Moondawg

By Guest

Pelecanimimus was a small ornithomimosaur, at about 2-2.5 m long (6.5 - 8 ft). Its skull was unusually long and narrow, with a maximum length of about 4.5 times its maximum height. It was highly unusual among ornithomimosaurs in its large number of teeth: it had about 220 very small teeth in total, with 7 premaxillary, about 30 maxillary, and 75 in the dentary. The teeth were heterodont, showing two different basic forms. The teeth in the front of the upper jaw were broad and D-shaped in cross section, while those further back were blade-like, and on the whole the teeth in the upper jaw were larger than those in the lower. All of its teeth were unserrated, and had a constricted "waist" between the crown and the root.

Only one other ornithomimosaur is known to possess teeth, Harpymimus, which had far fewer (eleven total, and only in the lower jaw). The presence of such a large number of teeth in Pelecanimimus, coupled with a lack of interdental space, was interpreted by Perez-Moreno et al. as an adaptation for cutting and ripping, a "functional counterpart of the cutting edge of a beak," as well as an exaptation leading to the toothless cutting edge found in later ornithomimosaurs.

The arms and hands of Pelecanimimus were more typical of ornithomimosaurs, with the ulna and radius bones in the lower arm tightly adhered close to the hand, which were hook-like and had fingers of equal length.

Soft-tissue impressions preserved by the exceptional preservational environment of the La Hoyas lagerstätten revealed the presence of a small skin or keratin crest on the back of the head, and a gular pouch similar to the much larger pouches found in modern pelicans, from which Pelecanimimus took its name. Pelecanimimus might have been much like a modern day crane, wading out in lakes or ponds using its claws and teeth to capture fish and then storing them in its skin flap. Some parts of the impressions revealed a smooth, skin-like surface, initially interpreted as lacking any ornamentation or feathers. Pelecanimimus was also the first ornithomimosaur discovered with a preserved hyoid apparatus (specialized bones in the neck).

A cladistic analyses by Makovicky et al. (2005) indicated that Pelecanimimus is the basalmost member of the Ornithomimosauria, less derived even than Harpymimus. A study by Kobayashi and Lü in 2003 indicated that these two species formed a basal arrangement of steps leading towards the more advanced ornithomimids (see cladogram below). The discovery of Pelecanimimus has played an important and surprising role in understanding the evolution of the Ornithomimosauria. To quote Pérez-Moreno et al., "The phylogenetic hypothesis...supports an unexpected approach, involving exaptation, which might explain the evolutionary process towards the toothless condition in Ornithomimosauria. Until now, a progressive reduction in the number of teeth has been considered as the most likely explanation: the primitive tetanurine theropods have up to 80 teeth with tall blade-like crowns, and the primitive ornithomimosaurs have only a few small teeth. The phylogenetic hypothesis suggests an alternative evolutionary process based on a functional analysis of increasing numbers of teeth. A high number of teeth with enough interdental space and properly placed denticles (as in troodontids) would be an adaptation for cutting and ripping. On the other hand, an excessive number of teeth with no interdental space (as in Pelecanimimus) would be a functional counterpart of the cutting edge of a beak. Thus, increasing the number of teeth would be an adaptation for cutting and ripping, as long as the space between adjacent teeth was preserved...while it would have the effect of working as a beak if spaces were filled with more teeth. The adaption to a cut-and-rip function therefore becomes an exaptation with a slicing effect, eventually leading to the cutting edge seen in most ornithomimosaurs."

133 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

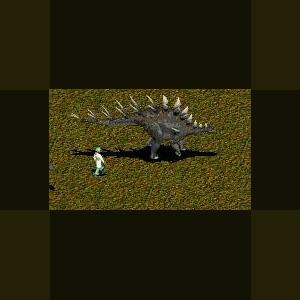

Dacentrurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Dacentrurus ("very sharp tail"), originally known as Omosaurus, was a large stegosaur of the late Jurassic Period (154 - 150 mya).

This dinosaur measured around 6 - 10 m (20 - 33 ft) in length.

When it was described by Richard Owen in 1875 as Omosaurus armatus, it was the first stegosaur ever discovered, although the genus name had to be changed as the name Omosaurus was preoccupied.

Fossil evidence has been found in Wiltshire and Dorset (including a vertebra ascribed to D. armatus in Weymouth[1]) in southern England, France and Spain and five more historically recent skeletons from Portugal. It had paired triangular plates down its spine, with four pairs of spikes on the end of the tail. This configuration closely resembles that of its relative, Kentrosaurus (see also: thagomizer). For unknown reasons, many books claim that Dacentrurus was a small stegosaur, when in fact finds such as a 1.5 m pelvis (measured at the acetabula) suggest that Dacentrurus was among the largest of them.

Other claimed species of Dacentrurus include D. durobrivensis (included with Lexovisaurus durobrivensis), D. phillipsi (sometimes mistakenly included with Priodontognathus phillipsi, due to having the same species name and a confused history), and D. vetustus (included with Lexovisaurus vetustus).

260 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Ornithomimus by Moondawg

By Guest

Ornithomimus velox was named on the basis of a foot and partial hand from the Maastrichtian Denver Formation, but better material has since been found in Canada, including the Edmontonian-age Ornithomimus edmontonicus and an excellent articulated specimen (species unknown) from Dinosaur Provincial Park. Other specimens of Ornithomimus have been discovered on the Eastern Coast of the USA

Like other ornithomimids, Ornithomimus is characterized by a three-toed foot, long slender arms and a long neck with a birdlike skull. It differs from other ornithomimids, such as Struthiomimus, in having very slender, straight hand and foot claws and in having metacarpals and fingers of similar lengths.Its hands are remarkably sloth-like in appearance, which led Henry Fairfield Osborn to suggest that they were used to hook branches during feeding.

Ornithomimus was 12 ft (3.5 meters) long, 7 feet (2.10 meters) high and weighed around 100-150 kg. It was bipedal and superficially resembled an ostrich, except for its long tail. It would have been a swift runner.

267 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Argentinosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Argentinosaurus (meaning "Argentina lizard") was a herbivorous sauropod dinosaur genus that was quite possibly the largest, heaviest land animal that ever lived. It developed on the island continent of South America during the middle of the Cretaceous Period (around 100 million years ago), after all of its more familiar Laurasian Jurassic kin — like Apatosaurus — had long disappeared.

Not much of Argentinosaurus has been recovered: just some back vertebrae, tibia, fragmentary ribs, and sacrum. One vertebra had a length of 1.3 meters and the tibia was about 155 centimeters (58 inches). However, the spectacular proportions of these bones and comparisons with other sauropod relatives allow paleontologists to estimate the size of the animal. Early reconstructions estimated Argentinosaurus at 35 meters (115 ft) in length and a weight of perhaps 80 to 100 tonnes. More recent estimates based on Saltasaurus, Opisthocoelicaudia and Rapetosaurus suggest sizes around 22-26 meters (72 - 85 ft).[1] It is the largest dinosaur for which there exists good evidence. Although it might have been smaller than Bruhathkayosaurus, which may have reached 44 meters (144 ft) in length and weighed 180 tons (however like Argentinosaurus it has been estimated shorter, at 28-34 meters (92-112 ft)), as well as the poorly known Amphicoelias fragilimus, which may have been up to 60 meters (200 ft) long, these estimates cannot be validated due to lack of evidence.

Vast wings on the vertebrae suited the attachment of massive muscles

The type species of Argentinosaurus, A. huinculensis, was described and published (by the Argentinian palaeontologists José F. Bonaparte and Rodolfo Coria) in 1993. Its more specific time-frame within the Cretaceous is the Albian to Cenomanian epochs, 112.2 to 93.5 million years ago. The fossil discovery site is in the Río Limay Formation in Neuquén Province, Argentina

Argentinosaurus is featured prominently in the permanent exhibition Giants of the Mesozoic at Fernbank Museum of Natural History in Atlanta, Georgia, USA. This display depicts a hypothetical encounter between Argentinosaurus and the carnivorous theropod dinosaur Giganotosaurus. Contemporary fossils of Cretaceous Period plants and animals are included in the exhibition, including two species of pterosaurs, providing a snapshot of a prehistoric ecosystem in what is now the modern Patagonia region of Argentina. At 123 feet (37 m) long, this skeletal reconstruction represents the largest dinosaur mount ever to be assembled.

603 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Hydrotherosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Hydrotherosaurus (meaning "water beast lizard") is an extinct genus of elasmosaurid plesiosaur from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Fresno County, California, measuring up to 13 m in length.

290 downloads

Updated

-

Deinonychus by Moondawg

By Guest

This 3.4 metre (11 ft) long dinosaur lived during the early Cretaceous Period (Aptian - Albian stages, 121 to 98.9 million years ago). Fossils of the only named species (D. antirrhopus) have been recovered from the U.S. states of Montana, Wyoming and Oklahoma, though teeth that may belong to Deinonychus have been found much farther east in Maryland.

(Terrible claw) refers to the unusually large, sickle-shaped talon on the second toe of each hind foot, which was probably held up off the ground while the dinosaur walked on the third and fourth toes. It was commonly thought that Deinonychus would kick with the sickle claw to slash at its prey but recent tests on reconstructions of similar Velociraptor talons suggest that the claw was used to stab, not slash. The species name antirrhopus means (counter balance), which refers to John Ostrom's idea about the function of the tail. As in other dromaeosaurids, the tail vertebrae have a series of ossified tendons and super - elongated bone processes. These features seemed to make the tail into a stiff counterbalance, but a fossil of the very closely related Velociraptor mongoliensis has an articulated tail skeleton that is curved laterally in a long S – shape. This suggests that, in life, the tail could swish to the sides with a high degree of flexibility In both the Cloverly and Antlers Formation, Deinonychus remains have been found closely associated with those of the ornithopod Tenontosaurus. Teeth discovered associated with Tenontosaurus specimens imply it was hunted or at least scavenged upon by Deinonychus.

Paleontologist John Ostrom's study of Deinonychus in the late 1960s revolutionized the way scientists thought about dinosaurs, igniting the debate on whether or not dinosaurs were warm-blooded. Before this, the popular conception of dinosaurs had been one of plodding, reptilian giants. Ostrom noted lightweight bones and raptorial claws on the feet, which revealed an active, agile predator.

343 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Kritosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Kritosaurus (meaning "separated lizard"; sometimes misinterpreted as "noble lizard", in reference to the presumed "Roman nose";

the nasal region was fragmented, disarticulated, and originally restored flat) is an incompletely known but historically important genus of hadrosaurid (duckbilled) dinosaur. It lived about 73 million years ago, in the Late Cretaceous of North and possibly South America. Its taxonomic history is convoluted, also incorporating Gryposaurus, Anasazisaurus, and Naashoibitosaurus; this tangle will remain unresolved until better remains of Kritosaurus are described. Despite the dearth of material, this herbivore appeared in dinosaur books until the 1990s, although what was usually represented was the much more completely known Gryposaurus, then thought to be a synonym.

Kritosaurus is only definitely determined from a partial skull and lower jaws, and associated undescribed postcranial remains. The greater portion of the muzzle and upper beak are missing, but additional reconstruction in the early 2000s using fragments from the skull that had not been placed before show part of a crest in front of the eyes; the form of the crest is unknown at this point. The length of the skull is estimated at 87 centimeters (34 in) from the tip of the upper beak to the base of the quadrate that articulates with the lower jaw at the back of the skull.

Potential diagnostic characteristics of Kritosaurus include a predentary (lower beak) without tooth-like crenulations,

a sharp downward bend to the lower jaws near the beak, and a heavy, somewhat rectangular maxilla (upper tooth-bearing bone). If it turns out to be the same as Anasazisaurus or Naashoibitosaurus, then the form of the complete crest is that of a tab or flange beginning in front of the eyes and rising between and above them, but not extended beyond them.

212 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Gyposaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Gryposaurus is similar to Kritosaurus, and for many years was regarded as the same genus. It is known from numerous skulls, some skeletons, and even some skin impressions that show it to have had pyramidal scales pointing out along the midline of the back. It is most easily distinguished from other duckbills by its narrow arching nasal hump, sometimes described as similar to a "Roman nose," and which may have been used for species or sexual identification, and/or combat with individuals of the same species. A large bipedal/quadrupedal herbivore around 9 meters long (30 ft), it may have preferred river settings.

Gryposaurus was a hadrosaurid of typical size and shape; one of the best specimens, the nearly complete type specimen of G. incurvimanus now on display at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, came from an animal about 8.2 meters long (27 feet). This specimen also has the best example of skin impressions for Gryposaurus, showing this dinosaur to have had several different types of scalation: pyramidal, ridged, limpet-shaped scutes upwards of 3.8 centimeters long (1.5 inches) on the flank and tail; uniform polygonal scales on the neck and sides of the body; and pyramidal structures, flattened side-to-side, with fluted sides, longer than tall and found along the top of the back in a single midline row.

The four named species of Gryposaurus differ in details of the skull and lower jaw.The prominent nasal arch found in this genus is formed from the paired nasal bones. In profile view, they rise into a rounded hump in front of the eyes, reaching a height as tall as the highest point of the back of the skull. The skeleton is known in great detail, making it a useful point of reference for other duckbill skeletons.

217 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Epidendrosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Epidendrosaurus

Epidendrosaurus ("upon-tree lizard") was a mid-Mesozoic (see "Provenance") maniraptoran dinosaur of the family Scansoriopterygidae. It was the first non-avian dinosaur found that had clear adaptations to an arboreal or semi-arboreal lifestyle--it is likely that it spent much of its time in trees. The only known specimen shows features indicating it was a juvenile. One distinctive feature of Epidendrosaurus is its elongated third finger, which is the longest on the hand, and bears a vague resemblance to the mammalian aye-aye (in most theropod dinosaurs, the second finger is the longest). Because of their juvenile nature, the size of a full-grown Epidendrosaurus is unknown. The only specimen known so far is a tiny, sparrow-sized creature. The type specimens of Epidendrosaurus contains the fossilized impression of feathers.

Kevin Padian and Alan Feduccia have treated this genus as a synonym of Scansoriopteryx, the former mistakenly treating Scansoriopteryx the junior synonym.

The only known specimen of Epidendrosaurus shows features indicating it was a juvenile. The specimen is partially disarticulated, and most bones are preserved as impressions in the rock slab, rather than three-dimensional structures.

One distinctive feature of Epidendrosaurus is its elongated third finger, which is the longest on the hand (nearly twice as long as the second finger), and may be analogous to the insect-digging finger of the mammalian aye-aye (in most theropod dinosaurs, the second finger is the longest). The only other dinosaur known to have a third finger longer than the first two is the closely related (and possibly synonymous) Scansoriopteryx. Epidendrosaurus is also notable for its wide, rounded jaws. The lower jaw contained at least twelve teeth, larger in the front of the jaws than in the back. The lower jaw bones may have been fused together, a feature otherwise known only in the oviraptorosaurs. The tail was long, six or seven times the length of the femur, and ended in a fan of feathers.

Because the specimen is a juvenile, the size of a full-grown Epidendrosaurus is unknown–the type specimen is a tiny, sparrow-sized creature.

Epidendrosaurus belongs to the family Scansoriopterygidae ("climbing wings"), though the exact taxonomic placement of this family is uncertain. Studies of dinosaur relationships have found Epidendrosaurus to be a close relative of true birds and a member of the clade Avialae.

There has been some degree of uncertainty regarding the status of the name Epidendrosaurus. The type specimen was described online in the online version of the journal Naturwissenschaften on 2002-08-21, while the identical print version (except for the date) was not published until 2002-09-30. However a very similar specimen named Scansoriopteryx heilmanni was described in the 2002-08-01 issue of The Dinosaur Museum Journal.

These two specimens are so similar that they may be the same genus, in which case a strict interpretation of Article 21 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) would give priority to Scansoriopteryx. However, the journal in which Scansoriopteryx appeared has a very small circulation and the issue was not distributed until roughly 2002-09-02, well after the electronic appearance of Epidendrosaurus. The conflict is used as an example in a proposed amendment to the ICZN that would consider electronic articles with Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs) that are subsequently available in print to qualify as "publication" for naming purposes. In scientific literature, the genus Scansoriopteryx has been treated as a senior synonym of Epidendrosaurus by Alan Feduccia and as a junior synonym by Kevin Padian.

The holotype specimen of Epidendrosaurus ninchengensis consists mostly of bone imprints in both part and counter part. Impressions indicate a relatively long tail, unlike the apparently short tail seen in Scansoriopteryx.

The fossilized skeleton of Epidendrosaurus was recovered from the Daohugou fossil beds of northeastern China. In the past, there has been some uncertainty regarding the age of these beds. Various papers have placed the fossils here anywhere from the Middle Jurassic period (169 million years ago) to the Early Cretaceous period (122 ma). The age of this formation has implications for the relationship between Epidendrosaurus and similar dinosaurs, as well as for the origin of birds in general. A Middle Jurassic age would mean that the bird-like dinosaurs in the Daohugou beds are older than the "first bird", Archaeopteryx, which was Late Jurassic in age. The provenance of Scansoriopteryx is uncertain, though Wang et al. (2006), in their study of the age of the Daogugou (see below), suggest that it probably hails from the same beds, and thus is likely a synonym of Epidendrosaurus.

A 2004 study by He et al. on the age of the Daohugou Beds found them to be Early Cretaceous, probably only a few million years older than the overlying Jehol beds of the Yixian Formation, where Scansoriopteryx was found. The 2004 study primarily used radiometric dating of a tuff within the Daohugou Bed to determine its age. However, a subsequent study by Gao & Ren took issue with the He et al. study. Gao and Ren criticized He et al. for not including enough specifics and detail in their paper, and also took issue with their radiometric dating of the Daohugou tuff. The tuff, Gao and Ren argued, contained crystals with a variety of diverse radiometric ages, some up to a billion years old, so using dates from only a few of these crystals could not determine the overall age of the deposits in which Epidendrosaurus (along with the other Daohugou fossils) were found. Gao and Ren went on to defend a Middle Jurassic age for the beds based on biostratigraphy (the use of index fossils) and the bed's relationship to a layer that is known to mark the Middle Jurassic-Late Jurassic boundary.

Another study, published in 2006 by Wang et al., found that the Tiaojishan Formation (159-164 million years old) underlies, rather than overlies, the Daohugou Beds. After taking into account the great similarity between the Daohugou fauna and the fauna of the Yixian Formation, the authors concluded that the Daohugou probably represents the earliest evolutionary stages of the Jehol Biota, and that it "belongs to the same cycle of volcanism and sedimentation as the Yixian Formation of the Jehol Group." Later in 2006, Liu et al. published their own study of the age of the Daohugou beds, this time using Zircon U-Pb dating on the volcanic rocks overlying and underlying salamander-bearing layers (salamanders are often used as index fossils). Liu et al. found that the beds formed between 164-158 million years ago, in the Middle to Late Jurassic.

Epidendrosaurus is cited as being an arboreal (tree-dwelling) maniraptoran based on the elongated nature of the hand and specializations in the foot.[3] The authors state that the long hand and strongly curved claws are adaptations for climbing and moving around among tree branches. They view this as an early stage in the evolution of the bird wing, stating that the forelimbs became well-developed for climbing, and that this development later lead to the evolution of a wing capable of flight. They state that long, grasping hands are more suited to climbing than to flight, since most flying birds have relatively short hands.

Zhang et al. also noted that the foot of Epidendrosaurus is unique among non-avian theropods. While the Epidendrosaurus specimen does not preserve a reversed hallux, the backward-facing toe seen in modern perching birds, its foot was very similar in construction to more primitive perching birds like Cathayornis and Longipteryx. These adaptations for grasping ability in all four limbs makes it likely that Epidendrosaurus spent a significant amount of time living in trees.

The type specimen of Epidendrosaurus also preserved faint feather impressions at the end of the tail, similar to the pattern found in the dromaeosaurid Microraptor. While the reproductive strategies of Epidendrosaurus itself remain unknown, several tiny fossil eggs discovered in Phu Phok, Thailand (one of which contained the embryo of a theropod dinosaur) may have been laid by a small dinosaur similar to Epidendrosaurus or Microraptor. The authors who described these eggs estimated the dinosaur they belonged to would have had the adult size of a modern Goldfinch.

166 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Eucoelophysis by Moondawg

By Guest

Eucoelophysis

Eucoelophysis (meaning "true hollow tail") is a genus of dinosauriform from the Late Triassic period of North America. It was assumed to be a coelophysid upon description, but a 2005 study by Nesbitt et al. found that it was actually a close relative of Silesaurus, which was independently supported by Ezcurra (2006), who found it to be the sister group to Dinosauria, and Silesaurus as the next most basal taxon.

However, the relationships of Silesaurus are uncertain. Dzik found it to be a dinosauriform (the group of archosaurs from which the dinosaurs evolved), but did not rule out the possibility that it represents a primitive ornithischian.

125 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Patagosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Patagosaurus

Patagosaurus (meaning "Patagonian lizard") was a large herbivorous dinosaur from the long-necked group Sauropoda. It reached the length of 18 meters. Similar to other primitive eusauropods, it was rather heavily build and similar to Cetiosaurus in general appearance. It is known from a dozen individuals, though some referred material may belong to another related dinosaur genus. It lived during the Callovian of the Middle Jurassic (163-161 mya) in what is now called Argentina. Other Argentinian dinosaurs living approximately at the same time were Piatnitzkysaurus, Condorraptor and Amygdalodon.

128 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Einiosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Einiosaurus

Einiosaurus is a medium-sized centrosaurine (“short-frilled”) ceratopsian from the Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) Two Medicine Formation of northwestern Montana. The generic epithet means 'buffalo lizard', in a combination of Blackfeet Indian and Latinized Ancient Greek and the specific epithet means 'forward-curving horn' in Latin and Ancient Greek.

Einiosaurus was a herbivorous dinosaur and grew to 6 meters in length. It is typically portrayed with a low, strongly forward-curving nasal horn that resembles a bottle opener, though this may only occur in some adults. Supraorbital (over-the-eye) horns are low and rounded if present at all, as opposed to ceratopsids with prominent supraorbital horns such as Triceratops. A pair of large spikes projects backwards from the relatively small frill.

Low-diversity and single-species bonebeds are thought to represent herds that may have died in catastrophic events, such as during a drought or flood. This is evidence that Einiosaurus, as well as other centrosaurine ceratopsians such as Pachyrhinosaurus and Centrosaurus, were herding animals similar in behavior to modern-day bison or wildebeest. In contrast, ceratopsine (“long-frilled”) ceratopsids, such as Triceratops and Torosaurus, are typically found singly, implying that they may have been somewhat solitary in life, though fossilized footprints may provide evidence to the contrary.

Like all ceratopsids, Einiosaurus had a complex dental battery capable of processing even the toughest plants.

Einiosaurus fossils are found in the upper part of the Two Medicine Formation of Montana, dating to the mid-late Campanian stage of the late Cretaceous Period, about 75-70 million years ago. Dinosaurs that lived alongside Einiosaurus include the basal ornithopod Orodromeus, hadrosaurids (such as Hypacrosaurus, Maiasaura, and Prosaurolophus), the ankylosaurs Edmontonia and Euoplocephalus, the tyrannosaurid Daspletosaurus (which appears to have been a specialist of preying on ceratopsians), as well as the smaller theropods Bambiraptor, Chirostenotes, Troodon, and Avisaurus. It also shared its habitat with other ceratopsids: Brachyceratops and Achelosaurus. Einiosaurus lived in a climate that was seasonal, warm, and semi-arid. Other fossils found with the Einiosaurus material include freshwater bivalves and gastropods, which imply that these bones were deposited in a shallow lake environment.

Einiosaurus is an exclusively Montanan dinosaur, and all its known remains are currently held at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana. At least 15 individuals of varying ages are represented by three adult skulls and hundreds of other bones from two low-diversity (in species) bonebeds, which were discovered by Jack Horner in 1985 and excavated from 1985 - 1989 by Museum of the Rockies field crews. These bonebeds were originally thought to contain a new species of Styracosaurus and are referred to as such in the comprehensive taphonomic study by Ray Rogers. In 1995 Scott D. Sampson formally described and named Einiosaurus procurvicornis from this material, as well as Achelousaurus horneri, also from a bonebed in this region.

The placement of Einiosaurus within Centrosaurinae is problematic due to the transitional nature of several of its skull characters, and its closest relatives are either Centrosaurus and Styracosaurus or Achelousaurus and Pachyrhinosaurus. The latter hypothesis is supported by Horner and colleagues, where Einiosaurus is the earliest of an evolutionary series in which the nasal horns gradually change to rough bosses, as in Achelousaurus and Pachyrhinosaurus which are the second and third in this series. The frills also grow in complexity.

Regardless of which hypothesis is correct, Einiosaurus appears to occupy an intermediate position with respect to the evolution of the centrosaurines.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einiosaurus

263 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Parksosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Parksosaurus

Parksosaurus ("William Parks's lizard") was a genus of hypsilophodont ornithopod dinosaur from the early Maastrichtian-age Upper Cretaceous Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, Canada. It is based on most of a partially articulated skeleton and partial skull, showing it to have been a small, bipedal, herbivorous dinosaur. It is one of the few described non-hadrosaurid ornithopods from the end of the Cretaceous in North America, existing around 70 million years ago.

Explicit estimates of the entire size of the animal have not been done, but William Parks found the hindlimb of his T. warreni to be about the same length overall as that of Thescelosaurus neglectus (93.0 centimeters (3.05 ft) for T. warreni versus 95.5 centimeters (3.13 ft) for T. neglectus), even though the shin was shorter than the thigh in T. neglectus, the opposite of T. warreni. Thus, the animal would have been comparable to the better-known Thescelosaurus in linear dimensions, despite proportional differences (around 1 meter (3.3 ft) tall at the hips, 2-2.5 meters (6.56-8.2 ft) long). The proportional differences probably would have made it lighter, though, as less weight was concentrated near the thigh. Like Thescelosaurus, it had thin cartilaginous plates along the ribs.

Parksosaurus has been considered to be a hypsilophodont since its description. Recent reviews have dealt with it with little comment, although David B. Norman and colleagues (2004), in the framework of a paraphyletic Hypsilophodontidae, found it to be the sister taxon to Thescelosaurus, and Richard Butler and colleagues (2008) found that it may be close to the South American genus Gasparinisaura. However, basal ornithopod phylogeny is poorly known at this point, albeit under study. Like Thescelosaurus, Parksosaurus had a relatively robust hindlimb, and an elongate skull without as much of an arched shape to the forehead compared to other hypsilophodonts.

Paleontologist William Parks described skeleton ROM 804 in 1926 as Thescelosaurus warreni, which had been discovered in what was then called the Edmonton Formation near Rumsey Ferry on the Red Deer River. When found, it consisted of a partial skull missing the beak region, most of the left pectoral girdle (including a suprascapula, a bone more commonly found in lizards, but which is believed to have been present in cartilaginous form in some ornithopods due to the roughened ends of their scapulae), the left arm except the hand, ribs and sternal elements, a damaged left pelvis, right ischium, the left leg except for some toe bones, articulated vertebrae from the back, hip, and tail, and a number of ossified tendons that sheathed the end of the tail. The body of the animal had fallen on its left side, and most of the right side had been destroyed before burial; in addition, the head had been separated from the body, and the neck lost. Parks differentiated the new species from T. neglectus by leg proportions; T. warreni had a longer tibia than femur, and longer toes.

Charles M. Sternberg, upon the discovery of the specimen he named Thescelosaurus edmontonensis, revisited T. warreni and found that it warranted its own genus (it was named in an abstract, which is not typical, but the specimen had already been thoroughly described). In 1940, he presented a more thorough comparison and found a number of differences between the two genera throughout the body. He assigned Parksosaurus to the Hypsilophodontinae with Hypsilophodon and Dysalotosaurus, and Thescelosaurus to the Thescelosaurinae. The genus attracted little attention until Peter Galton began his revision of hypsilophodonts in the 1970s. Parksosaurus received a redescription in 1973, wherein it was considered to be related to a Hypsilophodon\Laosaurus\L. minimus lineage. After this, it once again returned to obscurity.

George Olshevsky emended the species name to P. warrenae in 1992, because the species name honors a woman (Mrs. H. D. Warren), but outside of Internet sites, the original spelling has been preferred.

Parksosaurus shared the Horseshoe Canyon Formation with flat-headed hadrosaurid Edmontosaurus, spike-crested Saurolophus, and hollow-crested Hypacrosaurus, ankylosaurid Euoplocephalus, nodosaurid Edmontonia, horned dinosaurs Montanoceratops, Anchiceratops, Arrhinoceratops, and Pachyrhinosaurus, pachycephalosaurid Stegoceras, ostrich-mimics Ornithomimus and Struthiomimus, a variety of poorly-known small theropods including troodontids and dromaeosaurids, and the tyrannosaurids Albertosaurus and Daspletosaurus. The dinosaurs from this formation are sometimes known as Edmontonian, after a land mammal age, and are distinct from those in the formations above and below. The Horseshoe Canyon Formation is interpreted as having a significant marine influence, due to an encroaching Western Interior Seaway, the shallow sea that covered the midsection of North America through much of the Cretaceous.

In life, Parksosaurus, as a hypsilophodont, would have been a small, swift bipedal herbivore. It would have had a moderately long neck and small head with a horny beak, short but strong forelimbs, and long powerful hindlimbs.

120 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Yunnanosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Yunnanosaurus

Yunnanosaurus is a genus of prosauropod dinosaur from the Early to Middle Jurassic Period; a position in time that makes it one of the last prosauropods. It is closely related to Lufengosaurus. Known from two valid species, Yunnanosaurus ranged in size from 7 meters (23 feet) long and 2 m (7 ft) high to 13 m (42 ft) long in the largest species. It is known from over twenty skeletons, including two skulls, recovered from the Lufeng Formation of Yunnan, China.

Yang Zhongjian (aka C. C. Young) discovered the first Yunnanosaurus skeletons in the Lufeng Formation of Yunnan, China. The fossil find was composed over twenty incomplete skeletons, including two skulls, and were excavated by Tsun Yi Wang.

There were more than sixty spoon shaped teeth in the jaws of Yunnanosaurus, and were unique among prosauropods in that its teeth were self-sharpening because they "(wore) against each other as the animal fed." Scientists consider these teeth to be advanced compared to other prosauropods, as they share features with the sauropods.

However, scientists do not consider Yunnanosaurus to be especially close to the sauropods in phylogeny because the remaining portions of the animals body are distinctly prosauropod in design. This critical difference implies that the similarity in dentition between Yunnanosaurus and sauropods might be an example of convergent evolution.

type species, Y. huangi, was named by C. C. Young in 1942, and he erected the family Yunnanosauridae to contain it, though the family currently comprises only this genus. Young also named a second species, Y. robustus, in 1951, but this has since been included in the type species. The confusion in classification arose due to that the earliest specimens were of juveniles while the "Y. robustus" specimens represented fully grown adults.

In 2007, Lu and colleagues described another species of Yunnanosaurus, Y. youngi (named in honor of C. C. Young). In addition to various skeletal differences, at 13 meters (42 ft) long Y. youngi was significantly larger than Y. huangi (which reached only 7 meters (23 ft), and Y. youngi is found later in the fossil record, hailing from the Middle Jurassic.

179 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Technosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Technosaurus

Technosaurus (TEK-no-SAWR-us) was a Triassic ornithischian dinosaur. It was a small, lightly build herbivore reaching the length of 3 feet and running on its hind legs. The holotype apparently includes some prosauropod hatchling material. Technosaurus lived in North America and is named in honor of Texas Tech University. The type species, Technosaurus smalli, was named by Sankar Chatterjee in 1984.

Technosaurus is based on TTUP P9021, which initially consisted of a premaxilla (tip of the upper jaw), two lower jaw pieces, a back vertebra, and an astragalus. Technosaurus and its type species, T. smalli, were named by Sankar Chatterjee in 1984. He described it as a fabrosaurid,a clade of small early ornithischians now considered to have been an artificial grouping. Material from the quarry where P9021 was found is disassociated and comes from a variety of Late Triassic animals, which would prove problematic.

The genus was reviewed in 1991 by Paul Sereno, who interpreted the premaxilla and a fragment from the front of the lower jaw as pertaining to a hatchling prosauropod, and found the vertebra to be indeterminate and the astragalus an unidentifiable fragment. Thus, he restricted the remains to be considered Technosaurus to the second lower jaw piece, a posterior fragment. It was further reviewed in the light of new remains that spurred reevalutation of purported Triassic dinosaurs, particularly ornithischians named from tooth or jaw material. Irmis et al. (2007) agreed with the removal of the vertebra and astragalus, but found no characteristics that were unambiguously dinosaurian in the skull fragments. They noted similarities to Silesaurus in the jaw fragments Sereno had excluded, and themselves excluded the posterior fragment as actually belonging to the unusual rauisuchian Shuvosaurus.These authors would later restate their case, concluding that Technosaurus, defined only by the premaxilla and non-Shuvosaurus lower jaw fragment, was a valid, diagnostic genus, but could not be definitely classified beyond Archosauriformes incertae sedis, and was unlikely to be either an ornithischian or sauropodomorph dinosaur.

117 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Gojirasaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Gojirasaurus

Gojirasaurus is a genus of dinosaur named after Gojira (the Japanese name for Godzilla). It was discovered in Revuelto Creek, Quay County, New Mexico. The type specimen is a partial skeleton of a semi-adult, about 5.5 m (18 ft) long, which can be extrapolated to a weight of approximately 150–200 kg (330–440 lb). An adult would have been around 6.5 m (21 ft) long. It lived during the Norian age of the Late Triassic Period, between 220 and 209 million years ago. Gojirasaurus was a member of the Coelophysoidea, which were all small, early theropods. Gojirasaurus was perhaps the largest meat-eater know from the Triassic Period and enormous for its time. A serrated tooth, four ribs, four backbones, and a few other bones have been uncovered.

167 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Afrovenator by Moondawg

By Guest

Afrovenator ("African hunter") is a genus of megalosaurid theropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous Period of northern Africa.

It was a bipedal predator, with a mouthful of sharp teeth and three claws on each hand. Judging from the one skeleton known, this dinosaur was approximately 30 feet (9 meters) long from snout to tail tip.

The generic name comes from the Latin prefix afro- ("from Africa") venator ("hunter"). There is one named species, A. abakensis. The name refers to its predatory nature, and its location in Africa, specifically from In Abaka, the Tuareg name for the region of Niger where the fossils were found. The original description of both genus and species is found in a 1994 paper which appeared in the prestigious journal Science. The primary author was well-known American paleontologist Paul Sereno, with Jeffrey Wilson, Hans Larsson, Didier Dutheil, and Hans-Dieter Sues as coauthors.

The remains of Afrovenator were discovered in the Tiourarén Formation of the department of Agadez in Niger. The Tiourarén most likely represents the Hauterivian to Barremian stages of the Early Cretaceous Period, or approximately 136 to 125 million years ago (Sereno et al. 1994). The sauropod Jobaria, whose remains were first mentioned in the same paper which named Afrovenator, is also known from this formation.

Afrovenator is known from a single nearly complete skeleton, featuring most of the skull (minus the mandible, or lower jaw), parts of the spinal column, hands, and forelimbs, a nearly complete pelvis, and complete hind limbs. This skeleton is housed at the University of Chicago.

Most analyses place Afrovenator within Megalosauridae, which was formerly a "wastebasket family" which contained many large and hard-to-classify theropods, but has since been redefined in a meaningful way, as a sister taxon to the family Spinosauridae within the Spinosauroidea.

A 2002 analysis, focused mainly on the noasaurids, found Afrovenator to be a basal megalosaurid. However, it did not include Dubreuillosaurus (formerly Poekilopleuron valesdunesis), which could affect the results in that region of the cladogram (Carrano et al. 2002).

Other recent, more complete, cladistic analyses show Afrovenator in a subfamily of Megalosauridae with Eustreptospondylus and Dubreuillosaurus. This subfamily is either called Megalosaurinae (Allain 2002) or Eustreptospondylinae (Holtz et al. 2004). The latter study also includes Piatnitzkysaurus in this subfamily.

A few alternative hypotheses have been presented for Afrovenator's relationships.

382 downloads

Updated

-

Tsagantegia by Moondawg

By Guest

Tsagantegia

Tsagantegia (Tumanova, 1993; etymology = "of Tsagan-Teg") was a medium-sized member of the Ankylosauridae from the Upper Cretaceous Mongolia, during the Cenomanian stage. The holotype specimen (GI SPS N 700/17), a complete skull, was recovered from the Baynshiree Svita Formation (Cenomanian-Santonian), at the Tsagan-Teg ("White Mountain") locality, Dzun-Bayan, in the southeastern Gobi Desert, Mongolia. At this time, the genus is monotypic, including only the type species, T. longicranialis. The skull measures 30 cm. in length, with a maximum width of 25 cm.).Vickaryous et al. (2004) note that "Unlike other ankylosaurs, in Tsagantegia the cranial ornamentation is not subdivided into a mosaic of polygons but is amorphous." The quadratojugal and squamosal bosses are poorly developed, in contrast with other ankylosaurs. The skull was long and flat, smooth and bearing small horns.

The skull measures 30 centimeters (12 in) in length, with a maximum width of 25 centimeters (10 in). Vickaryous et al. (2004) note that "Unlike other ankylosaurs, in Tsagantegia the cranial ornamentation is not subdivided into a mosaic of polygons but is amorphous." The quadratojugal and squamosal bosses are poorly developed, in contrast with other ankylosaurs. The skull was long and flat, smooth and bearing small horns.

In their cladistic analysis of the Ankylosauria, Vickaryous et al. (2004) placed Tsagantegia at the base of the Ankylosauridae, as the sister group to all other ankylosaurids.

140 downloads

0 comments

Updated