Dinosaurs

Creatures from another age

241 files

-

Rutiodon by Moondawg

By Guest

Rutiodon

Rutiodon is an extinct genus of archosaurian reptile belonging to the phytosaur (plant lizard) group of the Triassic era. It was up to 3 m long.

Like other phytosaurs, Rutiodon strongly resembled a crocodile, with the only exception being the fact that its nostrils were positioned close to the eyes. Because of its enlarged front teeth, it most closely resembled the gharial. It probably caught fish and also snatched land animals from the waterside.It was an ambush predator. The animal is known from fossils in Europe (Germany and Switzerland as well as North America (Arizona, New Mexico, North Carolina, Texas). Its tail was covered with armour.

204 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Riojasaurus by Ghirin

By Guest

Riojasaurus ("Rioja lizard") was a prosauropod dinosaur from Argentina. The remains were found in La Roja Province. It was a heavily built animal.

Reference:

www.wikipedia.org

Created by Ghirin 2008

147 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Rinchenia by Moondawg

By Guest

Rinchenia

Rinchenia was a genus of Mongolian oviraptorid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period. Rinchenia mongoliensis was originally considered a species within the genus Oviraptor (named Oviraptor mongoliensis by Rinchen Barsbold in 1986), but a re-examination by Barsbold in 1997 found differences significant enough to warrant a separate genus. The name Rinchenia was coined for this new genus by Barsbold in 1997, though he did not describe it in detail, and the name remained a nomen nudum until used by Osmólska et al. in 2004.

Rinchenia is known from a single specimen (GI 100/32A) consisting of a complete skull and lower jaw, partial vertebral column, partial forelimbs and shoulder girdle, partial hind limbs and pelvis, and a furcula ("wishbone"). While Rinchenia was about the same size as Oviraptor (about 1.5 meters, or 5 ft long), several features of its skeleton, especially in the skull, show it to be distinct. It skeleton was more lightly built and less robust than that of Oviraptor, and while the crest of Oviraptor is indistinct because of poor fossil preservation, Rinchenia had a well-preserved, highly developed, dome-like casque which incorporated many bones in the skull that are free of the crest in Oviraptor.

183 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Rhamphosuchus by Moondawg

By Guest

Rhamphosuchus ("Beak crocodile") is an extinct relative of the modern gharial and false gharial.

It inhabited what is now the Indian sub-continent in the Miocene and Pliocene eras. It is only known from incomplete sets of fossils, mostly teeth and skulls, but palaeontologists estimate that it was one of the largest, if not the largest crocodylian that ever lived, reaching an estimated length of 15 to 18 m (50-60 ft). Another crocodylian, Purussaurus from the same era but living in Brazil is estimated to be of similar size from an equally incomplete fossil set. The only other crocodylians which even come close are the Late Cretaceous Deinosuchus and Early Cretaceous Sarcosuchus and also the strange planctivorous Mourasuchus which lived at the same time and in the same region with Purussaurus. As a relation to the modern gharial, Rhamphosuchus almost certainly ate fish, but whether of not it was capable of killing larger animals is unknown.

213 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Rapetosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

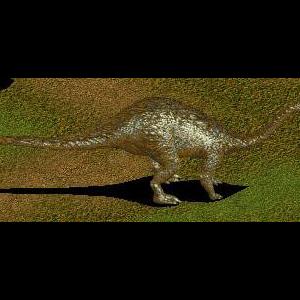

Rapetosaurus

Rapetosaurus is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived in Madagascar from 70 to 65 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous Period. Only one species (R. krausei) has been identified.

Like other sauropods, Rapetosaurus was a quadrupedal herbivore; it is calculated to have reached lengths of 15 metres.

Rapetosaurus was a fairly typical sauropod, with a short and slender tail, a very long neck and a huge, elephant-like body. Its head resembles the head of a diplodocid, with a long, narrow snout and nostrils on the top of its skull. It was an herbivore and its small, pencil-like teeth were good for ripping the leaves off trees but not for chewing.

It was fairly modest in size, for a titanosaur. The juvenile specimen measured 8 metres (26 ft) from head to tail, and "probably weighed about as much as an elephant", according to Kristina Curry Rogers. An adult would have been about twice as long (15 meters (49 ft) in length) which is still less than half the length of its gigantic kin, like Argentinosaurus and Paralititan.

During the early part of the Late Cretaceous all groups of sauropods, with the exception of the titanosaurs had gone extinct. The titanosaurs were the dominant herbivores of the Late Cretaceous on the southern continents. Their reign was cut short by the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event, which killed almost all the dinosaurs about 65 million years ago.

The discovery of Rapetosaurus, known by the single species Rapetosaurus krausei (pronounced rah-PAY-too-SORE-us KROW-sie and meaning 'Krause's mischievous giant lizard') marked the first time a titanosaur had been recovered with an almost perfectly intact skeleton, complete with skull. It has helped to clarify some difficult, century-old classification issues, among this large group of sauropod dinosaurs and provides a good baseline for the reconstruction of other titanosaurs that are known only from partial fossilized remains.

The discovery was published in 2001 by Kristina Curry Rogers and Catherine A. Forster in the scientific journal Nature. The nearly-complete skeleton is that of a juvenile and partial remains from three other individuals were also recovered.

The titanosaurs are the largest group of sauropods but are poorly represented in the fossil record. Other groups of sauropods, even small families like the brachiosaurids, are known from more complete remains. Until the discovery of Rapetosaurus, the 30 or so genera were represented by just a few bones, a partial skeleton or a skull. The first titanosaur, discovered in 1887, is still only known from a partial skeleton.

This has made it difficult to determine not just the relationship between different genera of titanosaur but even how the titanosaurs are related to other, higher-level groups like the macronarians (the group of "big nostril" sauropods, which include the titanosaurs, the nemegosaurids and the brachiosaurids). The whole taxon has been used as a dumping ground, with many genera labeled as incertae sedis (belonging to an unknown group), because not enough is known about them to classify them any further.

The Diplodocus-like skull has demonstrated that titanosaur skulls vary more than was previously believed. Most paleontologists believed that titanosaurs had box-like skulls with the nostrils midway up the snout, like the Camarasaurus, but Rapetosaurus has a long, low skull, with the nostrils on the top, similar to Diplodocus. This has allowed genera known only by Diplodocus-like skulls (like Quaesitosaurus and Nemegtosaurus and other nemegtosaurids) to be classified as macronarians rather than in Diplodocoidea.

Analysis of the rest of the skull and the body has also confirmed what was only previous speculated: that titanosaurs are most closely related to the brachiosaurids. "The discovery of this dinosaur is particularly exciting because it confirms a close relationship between the titanosaurs and brachiosaurs, something that could only be surmised previously," according to Rich Lane, of the National Science Foundation.

A complete skeleton can also serve as a baseline when reconstructing other titanosaurs from limited remains. This is the basis for new, revised estimates of the size of the super-giant titanosaurs.

The new species, Rapetosaurus krausei, was described in the August 2, 2001 issue of the scientific journal Nature, by Kristina Curry Rogers (then a graduate student under Catherine Forster and now employed by Macalester College, in St. Paul, Minnesota) and Catherine A. Forster, an Associate Professor at the Department of Anatomical Sciences of the State University of New York at Stony Brook, in Stony Brook, New York.

The Rapetosaurus is a member of the Nemegtosauridae family, which is within the unranked Titanosauria taxon.

The Madagascar dig

"Only a few of the tail bones were missing."

—Kristina Curry Rogers

The dig uncovered a partial skull (UA 8698, the holotype specimen), another partial skull, a juvenile skeleton missing only a few tail vertebrae, and an unrelated vertebra. The juvenile skeleton, in particular, is the most complete titanosaur skeleton ever recovered and the only one with a head still attached to the body.

The fossilized remains were found in the Mahajanga basin in northwest Madagascar, not far from the port city of Mahajanga. They were recovered from a layer of sandstone known as the Anembalemba Member, which is part of the Maevarano Formation. The rock formation has been dated to the Maastrichtian stage of the late Cretaceous, which means the fossilized bones are about 70 million years old.

They were found by a field team from the State University of New York at Stony Brook with the assistance of the local Universite d'Antananarivo. The team leader, David Krause, had been excavating fossils from the site since 1993.

A treasure-trove of bone

"We dug into the hillside, and the more you dug, the more bones we found".

—Kristina Curry Rogers

The Madadgascar location has produced a large number of significant paleontological discoveries for Krause and his team. As well as dinosaurs, fossils of fishes, frogs, turtles, snakes, crocodiles, birds, and mammals have been unearthed. Significant finds include:

The skull of Majungasaurus, a large carnivorous theropod like Tyrannosaurus, was discovered in 1996. It is similar to species found in India and Argentina, which indicate that land bridges between the fragments of the former supercontinent of Gondwana still existed in the late Cretaceous, far later than was previously believed. The most likely occurrence was a land bridge allowing animals to cross from South America to Antarctica, and then up to India and Madagascar. (See also Polar dinosaurs in Australia.)

Majungasaurus fossils have also been discovered with teeth marks that clearly come from the same species, making it the first dinosaur known to have practiced cannibalism.

Masiakasaurus is a new species of theropod, with very unusual teeth that stick straight out from its jaw.

A single, 70 million year old marsupial tooth. Madagascar was separated by water when the marsupials first evolved in the northern hemisphere, and there are no current species of marsupial on the island, which has revived the idea that colonies of animals might have somehow crossed vast stretches of water.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rapetosaurus

154 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Rainforest T-Rex by JohnT

By Admin Uploader

The T-Rex loves plenty of fresh meat, and needs the strongest fence to hold it. This Rainforest Tyrannosaurus Rex uses the same graphics as the in-game T-Rex, but with a change in habitat and object preferences, as well as different animal info. Since this T-Rex links directly to the graphics of the in-game T-Rex, you must have either DD or CC to use it. The in-game T-Rex will still be available in addition to this T-Rex.

79 downloads

- dinosaur

- rainforest

- (and 1 more)

0 comments

Updated

-

Quaesitosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Quaesitosaurus ('extraordinary lizard') is a Cretaceous titanosaurian sauropod (the last of this order) found by Kurzanov and Bannikov in 1983.

The type species is Quaesitosaurus orientalis. Quaesitosaurus grew to 23 meters long. It lived from 80 to 65 million years ago.

Quaesitosaurus (meaning "extraordinary lizard") is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod found by Kurzanov and Bannikov in 1983. The type species is Quaesitosaurus orientalis. Quaesitosaurus grew to 23 meters long. It lived from 85 to 70 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous (Santonian to Campanian ages). Its fossils, consisting solely of a partial skull, were found in the Barun Goyot Formation near Shar Tsav, Mongolia. Long, low and horse-like with frontally located peg-teeth, it is similar enough to the skulls of Diplodocus and its kin to have prompted informed speculation that the missing body was formed like those of diplodocids.

It is possible that Nemegtosaurus, also known from only skull material, is a very close relative of Quaesitosaurus, if not indeed a variation of the same animal.

135 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Purussaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Purussaurus was a giant caiman living in South America, 20 million years ago (Miocene). It is only known from skull material found in Peruvian Amazonia.

The skull is about 1.5 meters (5 ft), and paleontologists estimate that the whole body would have measured around 15 meters (50 ft), which means that Purussaurus is one of the largest crocodilians known to have ever existed. Two other extinct crocodilians, Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus, have similar proportions, but both are geologically much older, dating from the Early and Late Cretaceous, respectively. During the summer of 2005, a franco-peruvian expedition (the Fitzcarrald expedition) found new fossils of Purussaurus in Amazonia (600 km from Lima).

Purussaurus was a giant caiman living in South America during the Miocene epoch, 8 million years ago. It is known from skull material found in the Brazilian, Colombian and Peruvian Amazonia, besides in the north of Venezuela. The skull is about 1.5 meters (5 ft) long, and paleontologists estimate that the whole body would have measured around 12 meters, which means that Purussaurus is one of the largest crocodilians known to have ever existed. Two other extinct crocodilians, Sarcosuchus and Deinosuchus, have similar proportions, but both are geologically much older, dating from the Early and Late Cretaceous, respectively, and another from around the same era, the Rhamphosuchus, is also estimated to be of similar size. During the summer of 2005, a Franco-Peruvian expedition (the Fitzcarrald expedition) found new fossils of Purussaurus in Amazonia (600 km from Lima).

309 downloads

Updated

-

Protosolpuga by Serpyderpy

By Serpyderpy

Protosolpuga is an extinct species of solifugae known only from a single specimen that was discovered in Mazon Creek, Illinois, USA. While somewhat bigger than their real life size, these wonderful little creepy crawlies will make a nice addition to your paleozoic zoos!

83 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Protoceratops by Ghirin

By Guest

Protoceratops ("Before the horned-faces") is well known from numerous skeletons, ranging from young animals to adults. It was a common dinosaur from Cretaceous Mongolia.

Reference:

The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs by Dougal Dixon. 2006

www.wikipedia.com

Created by Ghirin 2006

509 downloads

Updated

-

Protoavis by Moondawg

By Guest

Protoavis is claimed to have been a 35 cm tall bird that lived in what is now Texas, USA,

between 225 and 210 million years ago. Though it existed far earlier than Archaeopteryx,

its skeletal structure is allegedly more bird-like. Protoavis has been reconstructed as

a carnivorous bird that had teeth on the tip of its jaws and eyes located at the front of

the skull, suggesting a nocturnal or crepuscular lifestyle. The fossil bones are too bad

ly preserved to allow an estimate of flying ability; although reconstructions usually

show feathers (see link below), judging from thorough study of the fossil material there

is no indication that these were present (Paul, 2002; Witmer, 2002).

However, this description of Protoavis assumes that Protoavis actually existed and,

if so, that it has been reconstructed correctly. Almost all paleontologists doubt that

Protoavis is a bird, or even a good species, because of the circumstances of its

discovery, and unconvincing avian synapomorphies in its fragmentary material.

When they were found at a Dockum Formation quarry in the Texas panhandle in 1984,

in a sedimentary strata of a Triassic river delta, the fossils were a jumbled cache of

disarticulated dinosaur and other bones that may reflect an incident of mass mortality

following a flash flood.

The discoverer, Sankar Chatterjee of Texas Tech University, was convinced that some of

these crushed bones belonged to two individuals - one old, one young - of the same

species. However, only a few parts were found, primarily a skull and some limb bones

which moreover do not well agree in their proportions respective to each other, and this

has led many to believe that the Protoavis fossil is chimeric, made up of more than one

organism: the pieces of skull appear like those of a coelurosaur, while most parts of

the limb skeleton suggest affinities to ceratosaurs and at least some vertebrae are most

similar to those of Megalancosaurus[2], which despite what its name may suggest is not a

dinosaur but rather an avicephalan diapsid:

"Everywhere one turns; the very fossils ascribed thereto challenge the validity of

Protoavis. The most parsimonious conclusion to be inferred from these data is that

Chatterjee's contentious find is nothing more than a chimera, a morass of long-dead

archosaurs."

If it really existed, Protoavis would raise interesting questions about when birds

began to diverge from the dinosaurs, but until better evidence is produced, the

animal's status currently remains uncertain. Furthermore, paleobiogeography suggests

that birds did not colonize the Americas until the Cretaceous; the most primitive

lineages of unequivocal birds found to date are all Eurasian. Certainly, the fossils

are most parsimoniously attributed to primitive dinosaurian and other reptiles as

outlined above. However, coelurosaurs and ceratosaurs are in any case not too distantly

related to the ancestors of birds and in some aspects of the skeleton not unlike them,

explaining how their fossils could be mistaken as avian; Archaeopteryx itself was

initially believed to be a small theropod dinosaur. Zhonghe Zhou sums up the matter:

"[Protoavis] has neither been widely accepted nor seriously considered as a Triassic

bird [... Witmer], who has examined the material and is one of the few workers to

have seriously considered Chatterjee’s proposal, argued that the avian status of

P. texensis is probably not as clear as generally portrayed by Chatterjee, and

further recommended minimization of the role that Protoavis plays in the discussion

of avian ancestry."

Sometimes it is claimed that Protoavis is a refutation of the hypothesis that birds

evolved from dinosaurs. But this is not true; the only consequence would be to push

back the point of divergence further back in time and possibly cause the dromaeosaurs to

be included in the bird clade. Note that at the time when these claims were originally

made, the affiliation of birds and maniraptoran theropods which today is well-supported

and generally accepted by most ornithologists was much more contentious; most Mesozoic

birds have only been discovered since then. Note also that Chatterjee himself has used

Protoavis to support a close relationship between dinosaurs and birds.

"As there remains no compelling data to support the avian status of Protoavis or

taxonomic validity thereof, it seems mystifying that the matter should be so contentious.

The author very much agrees with Chiappe in arguing that at present, Protoavis is i

rrelevant to the phylogenetic reconstruction of Aves. While further material from the

Dockum beds may vindicate this peculiar archosaur, for the time being, the case for

Protoavis is non-existent

168 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Protarcheopteryx by Ghirin

By Guest

Protarcheopteryx

Author: Ghirin

Protarcheopteryx ("Before Archeopteryx") was a feathered dinosaur from the Cretaceous lakeside environment of Liaoning, China. It was a contemporary of Caudipteryx.

190 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Protarchaeopteryx by Moondawg

By Guest

Protarchaeopteryx

Protarchaeopteryx was a turkey-sized feathered dinosaur from China. Well-developed, vaned feathers extended from the short, stubby tail; the hands were long and slender, and had three-fingered clawed hands. It appears to be one of the most primitive members of the Oviraptorosauria and the large incisor teeth suggest that it is closely related to, or synonymous with, Incisivosaurus. It was probably an herbivore or omnivore, but its hands are very similar to small carnivorous dinosaurs.

Protarchaeopteryx, known from the Jianshangou bed of the Yixian Formation, lived in the early Aptian age of the Early Cretaceous, 124.6 million years ago. It is probably more primitive than Archaeopteryx, making it a non-avian theropod dinosaur rather than a true avian bird. At around 1 metre (3.3 ft) in length, it would have been larger than Archaeopteryx. Protarchaeopteryx had symmetrical feathers on its arms. Since modern birds that have symmetrical feathers are flightless, and the skeletal structure of Protarchaeopteryx would not support flapping flight, it is assumed that it was flightless as well.

194 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Prosqualodon by Ghirin

By Guest

Prosqualodon by Ghirin

Prosqualodon ("Before the Shark-Tooth") was a toothed whale that resembled a modern dolphin in both size and build. It's teeth, however, were more like the ancient shark-toothed whales than the modern toothed whales. It lived during the Oligocene and the Miocene eras.

399 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Proganochelys by Ghirin

By Guest

Proganochelys by Ghirin

Proganochelys, the earliest known member of the tortoise family, lived in Europe during the Triassic period.

Its body is very similar to that of modern land tortoises, but Proganochelys could not retract its head or legs into its shell.

Reference:

The Simon and Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoris Creatures. Cox, Savage, Gardiner, Harrison, and Palmer, 1999.

230 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Procompsognathus by Moondawg

By Guest

Procompsognathus was a small archosaur that lived during the Late Triassic Period, about 222 to 219 million years ago.

Procompsognathus was named by Eberhard Fraas in 1913. He named the type species, P. triassicus, on the basis of a poorly-preserved skeleton found in Württemberg, Germany.

The name is derived from Compsognathus meaning 'elegant jaw' (Greek kompsos meaning 'elegant', 'refined' or 'dainty' and gnathos meaning 'jaw'), which was a later (Jurassic) dinosaur. The prefix pro implies 'before' or 'ancestor of', although this direct lineage is not supported by subsequent research.

While it is undoubtedly a small, bipedal carnivore, the extremely poor preservation of the only known Procompsognathus fossil makes its exact identity difficult to determine. It has historically been considered a theropod dinosaur, though some, such as Allen (2004), have found Procompsognathus to be a primitive, non-dinosaurian ornithodiran. Sereno and Wild (1992) stated that the holotype specimen consisted of fossils from two separate animals. They referred the skull to the primitive crocodylomorph Saltoposuchus, and the remainder of the skeleton to a ceratosaur related to Segisaurus. Rauhut and Hungerbuhler (2000) noted features of the vertebrae which suggest that Procompsognathus may be a coelophysid or ceratosaur, and Carrano et al. (2005), in their re-study of the related genus Segisaurus, found both Segisaurus and Procompsognathus to belong to the Coelophysidae within Dinosauria.

In Michael Crichton's novels Jurassic Park and The Lost World, Procompsognathus (often referred to as "compys") are one of the extinct species recreated through genetic engineering. Crichton portrays these dinosaurs as being venomous, a characteristic invented for the novel and not supported by fossil evidence. He also portrays them as scavengers and coprophagists (eaters of feces), useful in keeping the park clean of sauropod excrement. In the film adaptation of The Lost World, Procompsognathus were replaced with the distantly related coelurosaur Compsognathus. However, in the second film, Robert Burke refers to them as Compsognathus triassicus (triassicus being the type species of Procompsognathus).

169 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Proceratosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Proceratosaurus is a genus of medium-sized carnivorous theropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of England.

Originally thought to be an ancestor of Ceratosaurus due to the similar small crest on its snout, it is now considered a coelurosaur, one of the earliest known. Proceratosaurus may have been related to the ancestors of later forms such as Ornitholestes and the tyrannosaurs.

207 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Postosuchus by Moondawg

By Guest

Postosuchus was a basal archosaur which lived in what is now North America during the middle through to the late Triassic period (228-202 million years ago).

It was a rauisuchian, a cousin of crocodiles and came from the same ancestry as dinosaurs. Its name means "crocodile from Post", named after the Post Quarry in Texas, where many fossils of the species were found. It was one of the top predators of its area during the Triassic, larger than the small dinosaur predators of its time (such as Megapnosaurus and Coelophysis). It was a hunter which probably preyed on dicynodonts and many other creatures smaller than itself.

Postosuchus was a quadrupedal reptile with a wide skull and a long tail. It was about 6 meters long, 2 meters tall, and was held up by columnar legs (a quite uncommon feature in reptiles). A crocodile-like snout, filled with many large-sized dagger-like teeth, was used to kill its prey. Rows of protective plates covering its back formed a defensive shield.

288 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Polacanthus by Moondawg

By Guest

Polacanthus

Polacanthus, deriving its name from the Ancient Greek poly "many" and acantha "thorn" or "prickle", was an early armored, spiked, plant-eating ankylosaur from the early Cretaceous period. It lived 132 to 112 million years ago in what is now western Europe.

Polacanthus grew to between 4 to 5 metres (13 to 16 ft) long. It was a quadrupedal ornithischian or "bird-hipped" dinosaur. There are not many fossil remains of this creature, and some important anatomical features, such as its skull, are poorly known.

Polacanthus had a large sacral shield, a single fused sheet of dermal bone over its hips (sacral area) which was not attached to the underlying bone and decorated with tubercles. This feature is shared with other Polacanthine dinosaurs such as Gastonia and Mymoorapelta.

Polacanthus foxii was discovered by the Reverend William Fox on the Isle of Wight in 1865. It was an incomplete skeleton with the head, neck, anterior armour and forelimbs missing. Two other partial skeletons have since been found. The second known specimen was found and excavated by Dr William T. Blows in 1979, and is also in the London Natural History Museum. It is the first specimen to show neck vertebrae and anterior armour.

P. rudgwickensis was named in 1996 by Dr. William T. Blows, after review of some fossil material found in 1985 and thought to have been Iguanodon, which was on display at the Horsham Museum in Sussex. The material is fragmentary and includes several incomplete vertebrae, partial scapulocoracoid, the distal end of humerus, a nearly complete right tibia, rib fragments, and two osteoderms. P. rudgwickensis seems to have been about 30% larger than type species P. foxii and differs from it in numerous characters of the vertebrae and dermal armor. It is named after the village of Rudgwick in West Sussex and was discovered at a Rudgwick Brickworks Company quarry, at the quarry floor in gray-green marl beds of the Wessex Formation. Barremian age, approximately 124-132 million years ago.

174 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Podokesaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

The only fossils of Podokesaurus holyokensis (the full name given by Talbot) were recovered in 1911 by Mount Holyoke College professor of geology and geography, Mignon Talbot from a boulder near to the college. It was formally described that year based on a poorly preserved, incomplete fossil skeleton.

This fossil evidence suggests that it may not be a distinct genus but in fact a species of Coelophysis, standing 1 m (3 ft) long and 0.3 m (1 ft) high, and weighing 4 kg (10 lb). The matter is complicated because all the original fossil evidence for Podokesaurus holyokensis was destroyed in a fire and only casts remain in The Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

115 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Pistosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Pistosaurus longaevus is an extinct genus of aquatic sauropterygian reptile belonging to the plesiosaur order.

PISTOSAURUS

(pronounced PIST-oh-SAWR-us) Pistosaurus was a nothosaur, a reptile with flipper-like limbs that lived both on land and in the water. It was about 10 feet (3 m) long with a very long neck, four long, paddle-shaped flippers, a streamlined body, and many sharp, pointed teeth in long jaws. Fossils have been found in France and Germany. It lived during the mid-Triassic period. It was not dinosaur

229 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Pisanosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Pisanosaurus

Pisanosaurus mertii (the name comes from "Pisano", who was an associate of the finder, and "saurus" meaning lizard or reptile) is a primitive bipedal Ornithischian dinosaur from the Late Triassic.

Pisanosaurus was 3.2 feet (1 meter) in length and 12 inches (30.48 centimeters) in height. Its weight estimate is just under 8.8 pounds (four kilograms). These estimates vary due to the incompleteness of the fossil.

Pisanosaurus is known from a fragmented skeleton found in Argentina. It is very basal within Ornithischia; the postcrania seem to lack any good ornithischian synapomorphy; it has even been suggested the fossil is a chimera.

Pisanosaurus (meaning "Pisano lizard") is a genus of primitive ornithischian dinosaur from the Late Triassic of what is now South America. It was a bipedal herbivore described by Argentine paleontologist Rodolfo Casamiquela in 1967. Only one species, the type, Pisanosaurus mertii, is known, based on one partially complete skeleton. The fossils were discovered in Argentina's Late Triassic Ischigualasto Formation, from around 228 to 216.5 million years ago.

The exact classification of Pisanosaurus has been the topic of debate by scientists for over 40 years; the current consensus is that Pisanosaurus is the oldest known ornithischian, part of a diverse group of dinosaurs which lived during nearly the entire span of the Mesozoic Era.

Based on the known fossil elements, Pisanosaurus was a small, lightly-built dinosaur approximately 1 m (3 ft 3 in) in length and 30 cm (12 in) in height. Its weight was between 2.27–9.1 kg (5–20 lb). These estimates vary due to the incompleteness of the fossil. The tail of Pisanosaurus has been reconstructed as being as long as the rest of the body, based on other early ornithischians, but as a tail has not been recovered, this is speculative. It was bipedal and, like all ornithischians, was probably exclusively herbivorous.

Pisanosaurus mertii was described by Argentine paleontologist Rodolfo Casamiquela in 1967. The name Pisanosaurus honors Juan A. Pisano, an Argentine paleontologist, while saurus is derived from the Greek sa????, meaning "lizard". Pisanosaurus is known from a single fragmented skeleton found in Argentina. It is based on a specimen given the designation PVL 2577, which was discovered in the Ischigualasto Formation.

The fossils of Pisanosaurus were discovered in Argentina's Ischigualasto Formation. Originally dated to the Middle Triassic, this formation is now believed to belong to the Late Triassic Carnian stage, around 228 to 216.5 million years ago. Pisanosaurus shared its habitat with rhynchosaurs, cynodonts, dicynodonts, prestosuchids, ornithosuchids, aetosaurs, and primitive dinosaurs. The early carnivorous dinosaur Herrerasaurus lived in this area and at this time, and may have fed upon Pisanosaurus.

121 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Pinacosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Pinacosaurus ("plank lizard") is a genus of medium-sized ankylosaur dinosaurs that lived from the late Santonian to the late Campanian stages of the late Cretaceous period.

Pinacosaurus was a lightly-built, medium-sized ankylosaur with a long skull that reached a length of 5 meters (16 ft) Like all ankylosaurids, it had a bony club at the end of its tail which it used as a defensive weapon against predators such as Tarbosaurus. The most unusual element in the original specimen is the presence of two additional egg-shaped holes, one on top of the other, where the nostrils are normally found. The openings are characteristic of the genus, and the number varies: Godefroit et al. described four in 1999, and in 2003 a juvenile specimen with of five pairs of openings was described.

* Inspired by the Zoo Tek Brains Trust

158 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Pelecanimimus by Moondawg

By Guest

Pelecanimimus was a small ornithomimosaur, at about 2-2.5 m long (6.5 - 8 ft). Its skull was unusually long and narrow, with a maximum length of about 4.5 times its maximum height. It was highly unusual among ornithomimosaurs in its large number of teeth: it had about 220 very small teeth in total, with 7 premaxillary, about 30 maxillary, and 75 in the dentary. The teeth were heterodont, showing two different basic forms. The teeth in the front of the upper jaw were broad and D-shaped in cross section, while those further back were blade-like, and on the whole the teeth in the upper jaw were larger than those in the lower. All of its teeth were unserrated, and had a constricted "waist" between the crown and the root.

Only one other ornithomimosaur is known to possess teeth, Harpymimus, which had far fewer (eleven total, and only in the lower jaw). The presence of such a large number of teeth in Pelecanimimus, coupled with a lack of interdental space, was interpreted by Perez-Moreno et al. as an adaptation for cutting and ripping, a "functional counterpart of the cutting edge of a beak," as well as an exaptation leading to the toothless cutting edge found in later ornithomimosaurs.

The arms and hands of Pelecanimimus were more typical of ornithomimosaurs, with the ulna and radius bones in the lower arm tightly adhered close to the hand, which were hook-like and had fingers of equal length.

Soft-tissue impressions preserved by the exceptional preservational environment of the La Hoyas lagerstätten revealed the presence of a small skin or keratin crest on the back of the head, and a gular pouch similar to the much larger pouches found in modern pelicans, from which Pelecanimimus took its name. Pelecanimimus might have been much like a modern day crane, wading out in lakes or ponds using its claws and teeth to capture fish and then storing them in its skin flap. Some parts of the impressions revealed a smooth, skin-like surface, initially interpreted as lacking any ornamentation or feathers. Pelecanimimus was also the first ornithomimosaur discovered with a preserved hyoid apparatus (specialized bones in the neck).

A cladistic analyses by Makovicky et al. (2005) indicated that Pelecanimimus is the basalmost member of the Ornithomimosauria, less derived even than Harpymimus. A study by Kobayashi and Lü in 2003 indicated that these two species formed a basal arrangement of steps leading towards the more advanced ornithomimids (see cladogram below). The discovery of Pelecanimimus has played an important and surprising role in understanding the evolution of the Ornithomimosauria. To quote Pérez-Moreno et al., "The phylogenetic hypothesis...supports an unexpected approach, involving exaptation, which might explain the evolutionary process towards the toothless condition in Ornithomimosauria. Until now, a progressive reduction in the number of teeth has been considered as the most likely explanation: the primitive tetanurine theropods have up to 80 teeth with tall blade-like crowns, and the primitive ornithomimosaurs have only a few small teeth. The phylogenetic hypothesis suggests an alternative evolutionary process based on a functional analysis of increasing numbers of teeth. A high number of teeth with enough interdental space and properly placed denticles (as in troodontids) would be an adaptation for cutting and ripping. On the other hand, an excessive number of teeth with no interdental space (as in Pelecanimimus) would be a functional counterpart of the cutting edge of a beak. Thus, increasing the number of teeth would be an adaptation for cutting and ripping, as long as the space between adjacent teeth was preserved...while it would have the effect of working as a beak if spaces were filled with more teeth. The adaption to a cut-and-rip function therefore becomes an exaptation with a slicing effect, eventually leading to the cutting edge seen in most ornithomimosaurs."

133 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Pedopenna by Moondawg

By Guest

Pedopenna

Pedopenna ("foot feather") was a small, feathered, maniraptoran dinosaur from the Daohugou Beds in China. It is possibly older than Archaeopteryx, though the age of the Daohugou Beds where it was found is debated. Some estimates give an Early Cretaceous age, but the latest radiometric dating shows them to be late Middle Jurassic (Callovian) (c.140-168 mya).

The name Pedopenna refers to the long pennaceous feathers on the metatarsus; daohugouensis refers to the locality of Daohugou, where the holotype was found. Pedopenna daohugouensis probably measured 1 meter (3 ft) or less in length, but since this species is only known from the hind legs, the actual length is difficult to estimate. Pedopenna is classified as a paravian (Paraves), the group of maniraptoran dinosaurs that includes Aves and their closest relatives.

The feet of Pedopenna resembled those of the related troodontids and dromaeosaurids (which together form the group Deinonychosauria), though were overall more primitive. In particular, the second toe of Pedopenna was not as specialized as in deinonychosaurs. While Pedopenna did have an enlarged claw and slightly shortened second toe, it was not as highly developed as the strongly curved, sickle-like claws of its relatives.

Xu and Zhang, who interpreted the Daohugou fossil beds where Pedopenna was found as mid to late Jurassic in age, used the presence of such a primitive member of the avian lineage, in combination with many primitive members of closely related lineages there, to support the idea that birds originated in Asia.

The avian affinities of Pedopenna are further evidence of the dinosaur-bird evolutionary relationship. Apart from having a very bird-like skeletal structure in its legs, Pedopenna was remarkable due to the presence of long pennaceous feathers on the metatarsus (foot). Some deinonychosaurs are also known to have these 'hind wings', but those of Pedopenna differ from those of animals like Microraptor. Pedopenna hind wings were smaller and more rounded in shape. The longest feathers were slightly shorter than the metatarsus, at about 55 mm (2 in) long. Additionally, the feathers of Pedopenna were symmetrical, unlike the asymmetrical feathers of some deinonychosaurs and birds. Since asymmetrical feathers are typical of animals adapted to flying, it is likely that Pedopenna represents an early stage in the development of these structures. While many of the feather impressions in the fossil are weak, it is clear that each possessed a rachis and barbs, and while the exact number of foot feathers is uncertain, they are more numerous than in the hind-wings of Microraptor. Pedopenna also shows evidence of shorter feathers overlying the long foot feathers, evidence for the presence of coverts as seen in modern birds. Since the feathers show fewer aerodynamic adaptations than the similar hind wings of Microraptor, and appear to be less stiff, suggests that if they did have some kind of aerodynamic function, it was much weaker than in deinonychosaurs and birds. Xu and Zhang, in their 2005 description of Pedopenna, suggested that the feathers could be ornamental, or even vestigial. It is possible that a hind wing was present in the ancestors of deinonychosaurs and birds, and later lost in the bird lineage, with Pedopenna representing an intermediate stage where the hind wings are being reduced from a functional gliding apparatus to a display or insulatory function.

133 downloads

0 comments

Updated