Dinosaurs

Creatures from another age

241 files

-

Parasuchus by Moondawg

By Guest

Parasuchus was a genus of several crocodile-like semi-aquatic animals that lived in the Late Triassic, specifically the earlier Late Carnian period. The reptiles lived throughout Europe, North America, and North Africa.

190 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Cryptocleidus by Ghirin

By Guest

Cryptocleidus Author: Ghirin

Cryptocleidus ("Hidden Collar Bone") was a genus of plesiosaur from the late Jurassic period. Its fossils were found in Europe.

*Inspired by the Zoo Tycoon Brains Trust at the Zoo Tek Evolved Forums.

290 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Maiasaura by Ghirin

By Guest

Maiasaura

Author: Ghirin

http://www.zoo-tek.com/forums/index.php?download=782

Maiasaura ("Good Mother Lizard") formed large nesting colonies of up to 10,000 animals. Young Maiasaurs were cared for in the nest by adults until they were strong enough to follow the herd.

*Inspired by the Zoo Tycoon Brains Trust at the Zoo Tek Evolved Forums.*

342 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Yangchuanosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Yangchuanosaurus was a theropod dinosaur that lived in China during the Late Jurassic period, and was similar in size and appearance to its North American contemporary, Allosaurus.

It hails from the Upper Shaximiao Formation and was the largest predator in a landscape which included the sauropods Mamenchisaurus and Omeisaurus as well as the Stegosaurs Chialingosaurus, Tuojiangosaurus and Chungkingosaurus

In 1976, an almost complete skeleton of what was to be named Yangchuanosaurus shangyouensis was uncovered by a construction worker during the construction of the Shangyou Reservoir Dam in Yangshuan County in Sichuan Province. Since then further skeletons have been recovered.

Yangchuanosaurus shangyouensis reached about 7 metres long (23 ft) and had a skull around 80 cm long (32 in). Its relative Y. magnus grew larger still; up to 10 metres long (33 ft), with a skull up to 1 metre (3 ft) in length. There was a bony knob on its nose and multiple hornlets and ridges, similar to Ceratosaurus. It had a massive tail that was about half its length.

The original skeleton of Yangchuanosaurus shangyouensis is on display at the Municipal Museum of Chongqing, as is some material of Y. magnus. Another, recovered from Xuanhan County in Sichuan, is on display in the Beijing Museum of Natural History.

181 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Bambiraptor by Moondawg

By Guest

The Bambiraptor skeleton was discovered in 1995 by 14-year-old fossil hunter Wes Linster, who was looking for dinosaur bones with his parents near Glacier National Park in Montana. Linster told Time Magazine that he uncovered the skeleton on a tall hill and was amazed at his discovery. "I bolted down the hill to get my mom because I knew I shouldn't be messing with it", he said. The bones that Linster discovered on that hilltop led to the excavation of a skeleton that was approximately 95 percent complete. Because of its completeness Florida Paleontology Institute Director Martin Shugar compared it to the 'Rosetta Stone' that enabled archaeologists to translate Egyptian hieroglyphics. Yale paleontologist John Ostrom, who reintroduced the theory of bird evolution from dinosaurs after his 1964 discovery of Deinonychus in Wyoming, agreed, calling the specimen a "jewel", and telling reporters that the completeness and undistorted qualities of the bones should help scientists further understand the dinosaur-bird link. The specimen is currently housed at the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

During the conference where Bambiraptor was first introduced, the dinosaur reconstruction specialist Brian Cooley portrayed Bambiraptor as having feathers, despite the fact that no feathers were found with the fossil itself. His decision was influenced by the fact that because Bambiraptor within a cladistic analysis was a member of a group, Paraves, that contained feathered true birds and that was the sister taxon of Oviraptorosauria, a group that also had feathered forms (e.g. Caudipteryx), Bambiraptor most likely had feathers too due to phylogenetic bracketing. Most paleontologists support Cooley's view, and subsequent discoveries confirmed that small dromaeosaurid dinosaurs like Bambiraptor were fully covered in feathers.

Research done at Lamar State College in Orange, Texas has indicated that Bambiraptor may have had opposable front claws and a forelimb maneuverability that could reach its mouth. This would have given the animal the ability to "hold" food in its front limbs and place it in its mouth, in a similar manner to some modern-day small mammals.

Bambiraptor skull in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.Bambiraptor had a brain size in the lower range of modern birds. Because of its enlarged cerebellum, which may indicate higher agility and higher intelligence than other dromaeosaurs, David A. Burnham has hypothesized that Bambiraptor feinbergi may have been arboreal. Life in the trees may have required evolutionary pressure that resulted in a larger brain. Burnham also offers an alternative hypothesis that a larger brain could be selected for as a result of hunting more agile prey items such as lizards and mammals. Bambiraptor had the largest brain for its size of any dinosaur yet discovered, although the brain size may be due to its age, because juvenile animals tend to have larger brain-to-body ratios compared to adults. It also had very long arms and a well-developed wishbone.

233 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Dinictus by Moondawg

By Guest

Dinictis was a member of the Nimravid family, also known as "false saber-toothed cats". It had a sleek body (1.1 m. long), short legs (0.6 m. high) with only incompletely retractable claws, powerful jaws, and a long tail.

It was very similar to its close relative, Hoplophoneus. The shape of its skull is reminiscent of a felid skull rather than of the extremely short skull of the Machairodontinae. Compared with those of the more recent machairodonts, its upper canines were relatively small, but they nevertheless distinctly protruded from its mouth. Below the tips of the canines its lower jaw spread out in the form of a lobe.

Dinictis walked plantigrade (flat-footed), unlike modern felids. It looked like a small leopard and evidently its mode of life was similar to that of a leopard. It was probably not so particular about its food as its descendants, since reduction of the teeth was still in the early stages and Dinictis had not forgotten how to chew. Despite this, in its own environment it would have been a powerful predator.

It lived in the plains of North America around 40 million years ago in the late Eocene and early Oligocene. Fossils were found in Saskatchewan in Canada, and Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, Wyoming, and Oregon in the United States. Dinictis likely evolved from an early Miacis-like ancestor which lived in the Paleocene.

Made by request for Pukkie

253 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Stokesosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Stokesosaurus ("Stokes' lizard") was a small early tyrannosaur from the Late Jurassic period of Utah.

It was named after Utah geologist William Lee Stokes.

The holotype consists of a hip bone, originally thought to belong to the possible early

tyrannosaur Iliosuchus (Galton, 1976), as well as several vertebrae and a partial

braincase (Chure and Madsen, 1998). Another illium referred to this dinosaur (Foster and

Chure, 2000) is lost but may actually belong to the related Aviatyrannis, and a premaxilla

thought to belong to Illiosuchus (Madsen, 1974) is actually from Tanycolagreus.

Stokesosaurus and Tanycolagreus are about the same size, and it is possible that the

latter is a junior synonym of the former. However, the ilium (the best known element of

Stokesosaurus) of Tanycolagreus has never been recovered, making direct comparison

difficult.

Inspired by the Zoo Tek Brains Trust

156 downloads

Updated

-

Protoavis by Moondawg

By Guest

Protoavis is claimed to have been a 35 cm tall bird that lived in what is now Texas, USA,

between 225 and 210 million years ago. Though it existed far earlier than Archaeopteryx,

its skeletal structure is allegedly more bird-like. Protoavis has been reconstructed as

a carnivorous bird that had teeth on the tip of its jaws and eyes located at the front of

the skull, suggesting a nocturnal or crepuscular lifestyle. The fossil bones are too bad

ly preserved to allow an estimate of flying ability; although reconstructions usually

show feathers (see link below), judging from thorough study of the fossil material there

is no indication that these were present (Paul, 2002; Witmer, 2002).

However, this description of Protoavis assumes that Protoavis actually existed and,

if so, that it has been reconstructed correctly. Almost all paleontologists doubt that

Protoavis is a bird, or even a good species, because of the circumstances of its

discovery, and unconvincing avian synapomorphies in its fragmentary material.

When they were found at a Dockum Formation quarry in the Texas panhandle in 1984,

in a sedimentary strata of a Triassic river delta, the fossils were a jumbled cache of

disarticulated dinosaur and other bones that may reflect an incident of mass mortality

following a flash flood.

The discoverer, Sankar Chatterjee of Texas Tech University, was convinced that some of

these crushed bones belonged to two individuals - one old, one young - of the same

species. However, only a few parts were found, primarily a skull and some limb bones

which moreover do not well agree in their proportions respective to each other, and this

has led many to believe that the Protoavis fossil is chimeric, made up of more than one

organism: the pieces of skull appear like those of a coelurosaur, while most parts of

the limb skeleton suggest affinities to ceratosaurs and at least some vertebrae are most

similar to those of Megalancosaurus[2], which despite what its name may suggest is not a

dinosaur but rather an avicephalan diapsid:

"Everywhere one turns; the very fossils ascribed thereto challenge the validity of

Protoavis. The most parsimonious conclusion to be inferred from these data is that

Chatterjee's contentious find is nothing more than a chimera, a morass of long-dead

archosaurs."

If it really existed, Protoavis would raise interesting questions about when birds

began to diverge from the dinosaurs, but until better evidence is produced, the

animal's status currently remains uncertain. Furthermore, paleobiogeography suggests

that birds did not colonize the Americas until the Cretaceous; the most primitive

lineages of unequivocal birds found to date are all Eurasian. Certainly, the fossils

are most parsimoniously attributed to primitive dinosaurian and other reptiles as

outlined above. However, coelurosaurs and ceratosaurs are in any case not too distantly

related to the ancestors of birds and in some aspects of the skeleton not unlike them,

explaining how their fossils could be mistaken as avian; Archaeopteryx itself was

initially believed to be a small theropod dinosaur. Zhonghe Zhou sums up the matter:

"[Protoavis] has neither been widely accepted nor seriously considered as a Triassic

bird [... Witmer], who has examined the material and is one of the few workers to

have seriously considered Chatterjee’s proposal, argued that the avian status of

P. texensis is probably not as clear as generally portrayed by Chatterjee, and

further recommended minimization of the role that Protoavis plays in the discussion

of avian ancestry."

Sometimes it is claimed that Protoavis is a refutation of the hypothesis that birds

evolved from dinosaurs. But this is not true; the only consequence would be to push

back the point of divergence further back in time and possibly cause the dromaeosaurs to

be included in the bird clade. Note that at the time when these claims were originally

made, the affiliation of birds and maniraptoran theropods which today is well-supported

and generally accepted by most ornithologists was much more contentious; most Mesozoic

birds have only been discovered since then. Note also that Chatterjee himself has used

Protoavis to support a close relationship between dinosaurs and birds.

"As there remains no compelling data to support the avian status of Protoavis or

taxonomic validity thereof, it seems mystifying that the matter should be so contentious.

The author very much agrees with Chiappe in arguing that at present, Protoavis is i

rrelevant to the phylogenetic reconstruction of Aves. While further material from the

Dockum beds may vindicate this peculiar archosaur, for the time being, the case for

Protoavis is non-existent

168 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Proganochelys by Ghirin

By Guest

Proganochelys by Ghirin

Proganochelys, the earliest known member of the tortoise family, lived in Europe during the Triassic period.

Its body is very similar to that of modern land tortoises, but Proganochelys could not retract its head or legs into its shell.

Reference:

The Simon and Schuster Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoris Creatures. Cox, Savage, Gardiner, Harrison, and Palmer, 1999.

229 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Nemegtosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

It was named after the Nemegt Basin in the Gobi Desert, where the remains were found. It may have had a long, sloping head and, like most sauropods, had peg-shaped teeth.

The type species, Nemegtosaurus mongoliensis, was first described by Nowinski in 1971. A second species, N. pachi, was described by Dong in 1977, but is a nomen dubium.

173 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Dryptosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Dryptosaurus (meaning "tearing lizard") was a genus of primitive tyrannosaur that lived in Eastern North America during the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period.

An early painting of Dryptosaurus aquilunguis by Charles R. Knight illustrated fossil remains of Dryptosaurus aquilunguis. Dryptosaurus was 6.5 m long, 1.8 m high at the hips, and weighed about 1.2 tons. Like its relative Eotyrannus, it had relatively long arms with three fingers. Each of these fingers was tipped by a talon-like 8 inch claw.

In 1866, an incomplete skeleton (ANSP 9995) was found in New Jersey by workers in a quarry. Paleontologist E.D. Cope described the remains, naming the creature "Laelaps" ("storm wind", after the dog in Greek mythology that never failed to catch what it was hunting). "Laelaps" became one of the first dinosaurs described from North America (following Hadrosaurus, Aublysodon and Trachodon). Subsequently, it was discovered that the name "Laelaps" had already been given to a species of mite, and Cope's lifelong rival O.C. Marsh changed the name in 1877 to Dryptosaurus.

Before the discovery of Appalachiosaurus,it was classified in a number of theropod families. Originally considered a megalosaurid by Cope, it was later assigned to its own family (Dryptosauridae) by Marsh, and later found (through phylogenetic studied of the 1990s) to be a coelurosaur, though its exact placement within that group remained uncertain. The discovery of the closely related (and more complete) Appalachiosaurus made it clear that Dryptosaurus was a primitive tyrannosauroid.

173 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Dromaeosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

The first known Dromaeosaurus remains were first discovered by paleontologist Barnum Brown during a 1914 expedition to the Judith River Formation on behalf of the American Museum of Natural history. The area where these bones were collected is now part of Dinosaur Provincial Park in Alberta, Canada. The find consisted of a partial skull 9 inches in length and some foot bones. Several other bones, and dozens of isolated teeth, are also known from subsequent discoveries in Alberta and the western United States.[1]

Several species of Dromaeosaurus have been described, but Dromaeosaurus albertensis is the most complete specimen. Additionally, it is apparent that this genus is even rarer than other small theropods, although it was one of the first small theropods described based on reasonably good cranial material.

In 1969 similarities in anatomy between Dromaeosaurus and its relative Deinonychus were first observed. Based on the sickle-claws and commonalities in the skull, a new family, the dromaeosauridae was erected to house these two genera.[1] Since then, many new relatives of Dromaeosaurus have been found.

Dromaeosaurus differs from most other Dromaeosauridae in having a short, massive skull, a deep mandible, and robust teeth. In these respects Dromaeosaurus resembled the tyrannosaurs. The teeth tend to be more heavily worn than those of its relative Saurornitholestes, suggesting that its jaws were used for crushing and tearing rather than simply slicing through flesh.

It is possible that Dromaeosaurus was more of a scavenger than other small theropods, or it may be that Dromaeosaurus relied more heavily on its jaws to dispatch its prey. It was probably better suited to tackling large prey than the more lightly built Saurornitholestes.

The relationships of Dromaeosaurus are unclear. Although its rugged build gives it a primitive appearance, it was actually a very specialized animal. It is usually given its own subfamily, the Dromaeosaurinae; this group is thought to include Utahraptor, Achillobator, Adasaurus and perhaps Deinonychus.

However, the relationships of dromaeosaurs are still in a state of flux. "Dromaeosaurus Morphotype A" is the designation given to a series of unusual, ridged dromaeosaur teeth from Alberta. These teeth probably do not belong to Dromaeosaurus, although it is unclear from what animal they do come.

201 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Compsognathus by Moondawg

By Guest

Compsognathus (pronounced kompsos"elegant", "refined" or "dainty", and gnathos"jaw") was a small, bipedal, carnivorous theropod dinosaur.

The animal was the size of a turkey and lived around 150 million years ago, the early Tithonian stage of the late Jurassic Period, in what is now Europe.

Paleontologists have found two well-preserved fossils, one in Germany in the 1850s and the second in France more than a century later.

Many popular presentations still describe Compsognathus as a "chicken-sized" dinosaur because of the small size of the German specimen, which is now believed to be a juvenile form of the larger French specimen. Compsognathus is one of the few dinosaurs for which the diet is known with certainty: the remains of small, agile lizards are preserved in the bellies of both specimens. Teeth discovered in Portugal may be further fossil remains of the genus.

Although not recognized as such at the time of its discovery, Compsognathus is the first dinosaur known from a reasonably complete skeleton. Today, C. longipes is the only recognized species, although the larger specimen discovered in France in the 1970s was once thought to belong to a separate species, C. corallestris. Until the 1980s and 1990s, Compsognathus was the smallest known dinosaur and the closest supposed relative of the early bird Archaeopteryx. Thus, the genus is one of the few dinosaur genera to be well known outside of paleontological circles.

273 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Bernissartia by Moondawg

By Guest

Bernissartia is one of the smallest crocodylians that ever lived. It resembled modern species and was probably semi-aquatic. It had long, pointed teeth at the front of the jaws would have been of use in catching fish, while the broad and flat teeth at the back of its jaws would have facilitated crushing hard food, such as shellfish and possibly bones. It lived during the early Cretaceous in modern day England and Belgium.

270 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Microraptor by Moondawg

By Guest

Microraptor had two sets of wings, on both its fore- and hind legs. The long feathers on the legs of Microraptor were true flight feathers as seen in modern birds, with asymmetrical vanes on the arm, leg, and tail feathers. As in bird wings, Microraptor had both primary (anchored to the hand) and secondary (anchored to the arm) flight feathers. This standard wing pattern was mirrored on the hind legs, with flight feathers anchored to the upper foot bones as well as the upper and lower leg. It had been proposed by Chinese scientists that the animal glided, and probably lived in trees, pointing to the fact that wings anchored to the feet of Microraptor would have hindered their ability to run on the ground, and suggest that all primitive dromaeosaurids may have been arboreal.

Sankar Chatterjee determined in 2005 that, in order for the creature to glide or fly, the wings must have been split-level (like a biplane) and not overlayed (like a dragonfly), and that the latter posture would have been anatomically impossible. Using this biplane model, Chatterjee was able to calculate possible methods of gliding, and determined that Microraptor most likely employed a phugoid style of gliding--launching itself from a perch, the animal would have swooped downward in a deep 'U' shaped curve and then lifted again to land on another tree. The feathers not directly employed in the biplane wing structure, like those on the tibia and the tail, could have been used to control drag and alter the flight path, trajectory, etc. The orientation of the hind wings would also have helped the animal control its gliding flight. Chatterjee also used computer algorithms that test animal flight capacity to test whether or not Microraptor was capable of true, powered flight, in addition to passive gliding. The resulting data showed that Microraptor did have the requirements to sustain level powered flight, so it is theoretically possible that the animal flew on occasion in addition to gliding.

Some paleontologists have suggested that feathered dinosaurs used their wings to parachute from trees, possibly in order to attack or ambush prey on the ground, as a precursor to gliding or true flight. In their 2007 study, Chatterjee and Templin tested this hypothesis as well, and found that the combined wing surface of Microraptor was too narrow to successfully parachute to the ground without injury from any significant height. However, the authors did leave open the possibility that Microraptor could have parachuted short distances, as between closely spaced tree branches.

Chatterjee and Templin also ruled out the possibility of a ground-based takeoff. Microraptor lacked the necessary adaptations in its shoulder joint to lift its front wings high enough vertically to generate lift from the ground, and the authors argued that a ground-based takeoff would have damaged flight feathers on the feet. This leaves only the possibility of launching from an elevated perch, and the authors noted that even modern birds do not need to use excess power when launching from trees, but use the downward-swooping technique they found in Microraptor.

The unique wing arrangement found in Microraptor raised the question of its importance to the origin of flight in modern birds--did avian flight go through a four-winged stage, or were four-winged gliders like Microraptor an evolutionary side-branch that did not leave descendants? As early as 1915, some scientists had argued that the evolution of bird flight may have gone through a four-winged (or tetrapteryx) stage. Chatterjee and Templin did not take a strong stance on this possibility, noting that both a conventional interpretation and a tetrapteryx stage are equally possible. However, based on the presence of unusually long leg feathers in various feathered dinosaurs, Archaeopteryx, and some modern birds such as raptors, as well as the discovery of Pedopenna (another dinosaur with long primary feathers on its feet), the authors argued that the current body of evidence, both from morphology and phylogeny, suggests that bird flight did shift at some point from shared limb dominance to front-limb dominance, and that all modern birds may have evolved from four-winged ancestors, or at least ancestors with unusually long leg feathers relative to the modern configuration.

The naming of Microraptor is controversial, because of the unusual circumstances of its first description. The first specimen to be described was part of a chimeric specimen , a patchwork of unrelated feathered dinosaur species assembled from multiple specimens in China and smuggled to the USA for sale. After the forgery was revealed by Xu Xing of Beijing's Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Storrs L. Olson, curator of birds in the National Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution, published a description of the tail in an obscure journal, giving it the name Archaeoraptor liaoningensis in an attempt to remove the name from the paleornithological record by assigning it to the part least likely to be a bird. However, Xu had discovered the remainder of the specimen from which the tail had been taken and published a description of it later that year, giving it the name Microraptor zhaoianus.

Since the two names designate the same individual as the type specimen, Microraptor zhaoianus is a junior objective synonym of Archaeoraptor liaoningensis and the latter, if valid, has priority. So, according to some interpretations of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, the valid name for this dinosaur probably is Archaeoraptor liaoningensis Olson 2000. However, there is some doubt whether Olson in fact succeeded in meeting all the formal requirements for establishing a new taxon. Most paleontologists are unwilling to use the name Archaeoraptor regardless of the precise legal status of the name. This is firstly because that name is strongly associated with the fraud and the National Geographic scandal and secondly because they view Olson's use of the name as attempted nomenclatural sabotage and do not want to support it. The name Microraptor zhaoianus Xu et al., 2000 has therefore almost attained universal currency.

293 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Pachyrhinosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Pachyrhinosaurus

Pachyrhinosaurus (meaning "thick-nosed reptile") is a genus of ceratopsid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of North America. The first examples were discovered by Charles M. Sternberg in Alberta, Canada, in 1946, and named in 1950. Twelve partial skulls and a large assortment of fossils have been found in total in Alberta and Alaska. A great number were not available for study until the 1980s, resulting in a relatively recent increase of interest in the Pachyrhinosaurus. Instead of horns, the skull bears massive, flattened bosses, the largest being over the nose. These were probably used in butting and shoving matches, as in musk oxen. A single pair of horns grew from the frill and extended upwards. It appears that that both the shape and size of the frill was highly individualized, reliant on gender and perhaps other factors. Pachyrhinosaurus is most closely related to Achelousaurus.

Pachyrhinosaurus was 5.5 to 7 meters (18 to 23 ft) long. It weighed about four tons. It was herbivorous and possessed strong cheek teeth to help it chew tough, fibrous plants.

The type species, Pachyrhinosaurus canadensis, was described in 1950 by Charles Mortram Sternberg.

In 1972, Grande Prairie, Alberta science teacher Al Lakusta found a large bonebed along Pipestone Creek in Alberta. When the area was finally excavated between 1986 and 1989 by staff and volunteers of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, paleontologists discovered an amazingly large and dense selection of bones--up to 100 per square meter, with a total of 3500 bones and 14 skulls. This was apparently the site of a mass mortality, perhaps a failed attempt to cross the river during a flood. Found amongst the fossils were the skeletons of four distinct age groups ranging from juveniles to full grown dinosaurs, indicating that the Pachyrhinosaurus did indeed care for their young.

The adult skulls had both convex and concave bosses as well as unicorn-style horns on the parietal bone just behind their eyes. The concave boss types might be related to erosion only and not reflect male/female differences. In 2008, a detailed monograph describing the skull of the Pipestone Creek pachyrhinosaur, and penned by Philip J. Currie, Wann Langston, Jr., and Darren Tanke, classified the specimen as a second species of Pachyrhinosaurus, named P. lakustai after its discoverer

282 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Barosaurus by Ghirin

By Guest

Barosaurus (“Heavy Lizard”) was a member of the Diplodocidae and a close relative of both Apatosaurus and Diplododus. This particular family of sauropods was named after the beam-shaped bones in their tails.

Barosaurus fossils have been been found in two locations. It ws first identified in western North America. Recently, Barosaurus fossils have been discovered in Tanzania.

References:

http://dinosauricon.com/genera/barosaurus.html

Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Creatures. Malam and Parker, 2002

Dinosaurs. Parker, 2003

Created by Ghirin 2004

254 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Neovenator by Moondawg

By Guest

Neovenator ("New-Hunter") is a genus of allosauroid dinosaur. Since its discovery on the Isle of Wight, UK, it has become one of the best-known large carnivorous dinosaurs in Europe.

Neovenator was at first considered possibly a new species of Megalosaurus. It measured approximately 7.5 meters in length, and was of a gracile build. It lived during the Barremian stage of the Cretaceous Period.

The first bones of the type species were discovered in 1978, in the chalk cliffs of southwest Isle of Wight. It was much later (1996) that more bones from this specimen were found. Excavations undertaken by Dr Steve Hutt and his team have so far revealed approximately 70% of the skeleton.

At the time that it was described, by Steve Hutt, Martill and Barker in 1996, it was the only known allosaurid in Europe. It is currently considered to be closely related to Allosaurus, Acrocanthosaurus and Giganotosaurus.

A life-sized, animatronic model of the animal is on display at the Dinosaur Isle attraction in the Isle of Wight.

166 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

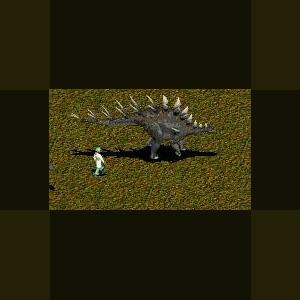

Dacentrurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Dacentrurus ("very sharp tail"), originally known as Omosaurus, was a large stegosaur of the late Jurassic Period (154 - 150 mya).

This dinosaur measured around 6 - 10 m (20 - 33 ft) in length.

When it was described by Richard Owen in 1875 as Omosaurus armatus, it was the first stegosaur ever discovered, although the genus name had to be changed as the name Omosaurus was preoccupied.

Fossil evidence has been found in Wiltshire and Dorset (including a vertebra ascribed to D. armatus in Weymouth[1]) in southern England, France and Spain and five more historically recent skeletons from Portugal. It had paired triangular plates down its spine, with four pairs of spikes on the end of the tail. This configuration closely resembles that of its relative, Kentrosaurus (see also: thagomizer). For unknown reasons, many books claim that Dacentrurus was a small stegosaur, when in fact finds such as a 1.5 m pelvis (measured at the acetabula) suggest that Dacentrurus was among the largest of them.

Other claimed species of Dacentrurus include D. durobrivensis (included with Lexovisaurus durobrivensis), D. phillipsi (sometimes mistakenly included with Priodontognathus phillipsi, due to having the same species name and a confused history), and D. vetustus (included with Lexovisaurus vetustus).

260 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Sinotherium by Moondawg

By Guest

Sinotherium ("Chinese Beast") was a genus of single-horned rhinoceri of the late Miocene and Pliocene.

It was ancestral to Elasmotherium, and its fossils have been found in western China. Sinotherium diverged from the ancestral genus, Iranotherium, first found in Iran, during the early Pliocene. Some experts prefer to lump Sinotherium, and Iranotherium into Elasmotherium.

258 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Calsoyasuchus by Moondawg

By Guest

Calsoyasuchus

Calsoyasuchus (meaning "[Dr. Kyril] Calsoyas' crocodile") is a genus of goniopholidid mesoeucrocodylian that lived in the Early Jurassic. Its fossilzed remains were found in the Sinemurian-Pliensbachian-age Kayenta Formation on Navajo Nation land in Coconino County, Arizona, United States. Formally described as C. valliceps, it is known from a single incomplete skull which is unusually derived for such an early crocodile relative. This genus was described in 2002 by Ronald Tykowski and colleagues; the species name means "valley head" and refers to a deep groove along the midline of the nasal bones and frontal bones.

The holotype skull that would be named Calsoyasuchus was discovered in 1997 by members of an expedition composed of crews from Texas Memorial Museum of the University of Texas at Austin, the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, and the Seba Dalkai Navajo Nation School. It was found in the middle third of the silty facies of the Kayenta Formation, near the Adeii Eechii Cliffs. The skull is missing the lower jaws, part of the palate, most of the suspensorium (the bones that make up the region where the upper and lower jaws articulate), and the occiput and braincase. Sutures between the skull bones are mostly fused. As preserved, it is about 38.0 centimeters (15.0 in) long, making its owner a moderately sized animal.

The skull was long, low, and curved so that both extremities were higher than the middle. The premaxilla bones that formed the end of the snout were enlarged to form a wide tip; there were at least four teeth in the right premaxilla and five in the left. The left maxilla (main tooth-bearing bone of the upper jaw) is more complete than the right, and had at least 29 teeth. There was a deep groove along the midline of the nasals and the frontals; the frontals were fused into a single bone, as is seen in other adult mesoeucrocodylians. Unlike derived neosuchians, it had external antorbital fenestrae. Tykowski and colleagues subjected the skull to CT scanning, which revealed internal cavities and air passages, and showed that it had a double-walled secondary palate similar to that of true crocodylians, and similar pneumatic cavities as well.

Tykowski and colleagues performed a cladistic phylogenetic analysis with their new taxon, and found that it grouped with Goniopholis, Sunosuchus, and, most closely, with Eutretauranosuchus in a weakly supported clade, Goniopholididae. They noted that the skull of Calsoyasuchus is very similar to some goniopholid skulls from the younger, Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. Calsoyasuchus pushes back the earliest occurrence of goniopholids from the Late Jurassic into the Early Jurassic, and not only helps to bridge a temporal gap between groups of crocodyliforms, but also a morphological gap. It also implies that some groups of crocodyliforms have long undiscovered histories.

During the Sinemurian and Pliensbachian ages of the Early Jurassic, the Kayenta Formation had a diverse fauna, with the remains of caecilians, frogs, turtles, at least five other taxa of crocodylomorphs, pterosaurs, theropod, sauropodomorph, and ornithischian dinosaurs, and early relatives of mammals (tritylodontids and morganucodontids).

251 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Sarcosuchus Imperator by Moondawg

By Guest

Sarcosuchus meaning 'flesh crocodile' and commonly called "SuperCroc", is an extinct genus of crocodile.

It dates from the early Cretaceous Period of what is now Africa and is one of the largest giant crocodile-like reptiles that ever lived. It was almost twice as long as the largest modern crocodile and weighed up to 10 times as much.

Until recently, all that was known of the genus was a few fossilised teeth and armour scutes, which were discovered in the Sahara Desert by the French paleontologist Albert-Félix de Lapparent, in the 1940s or 1950s. However, in 1997 and 2000, Paul Sereno discovered half a dozen new specimens, including one with about half the skeleton intact and most of the spine. All of the other giant crocodiles are known only from a few partial skulls, so which is actually the biggest is an open question.

When fully mature, Sarcosuchus is believed to have been as long as a city bus (11.2–12.2 meters or 37–40 ft) and weighed up to 8 tonnes (8.75 tons). The largest living crocodilian, the saltwater crocodile, is less than two-thirds of that length (6.3 meters or 20.6 ft is the longest confirmed individual) and a small fraction of the weight (1,200 kg, or 1.3 tons).

The very largest Sarcosuchus is believed to have been the oldest. Osteoderm growth rings taken from an 80% grown individual (based on comparison to largest individual found) suggest that Sarcosuchus kept growing throughout its entire 50–60 year average life span (Sereno et al., 2001). Modern crocodiles grow at a rapid rate, reaching their adult size in about a decade, then growing more slowly afterwards.

Its skull alone was as big as a human adult (1.78 m, or 5 ft 10 inches). The upper jaw overlapped the lower jaw, creating an overbite. The jaws were relatively narrow (especially in juveniles). The snout comprises about 75% of the skull's length (Sereno et al., 2001).

The huge jaw contained 132 thick teeth (Larsson said they were like "railroad spikes. The teeth were conical, adapted for grabbing and holding; instead of narrow, adapted for slashing (like the teeth of some land-dwelling carnivores), and more like that of true crocodilians. Sarcosuchus could probably exert a force of 80 kN (18,000 lbf) with its jaw, making it very unlikely that prey could escape.

It had a row of bony plates or osteoderms, running down its back, the largest of which were 1 m (3 ft) long. The scutes served as armour and may have helped support its great mass, but also restricted its flexibility.

Sarcosuchus also had a strange depression at the end of its snout. Called a bulla, it has been compared to the ghara seen in gharials. Unlike the ghara, though, the bulla is present in all Sarcosuchus skulls that have been found so far. This suggests it was not a sexually selected character (only the male gharial has a ghara). The purpose of this structure remains enigmatic. Sereno and others asked various reptile researchers what their thoughts on this bulla were. Opinions ranged from it being an olfactory enhancer to being connected to a vocalization device.

333 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Variraptor by JohnT

By Admin Uploader

As a cousin of the Velociraptor, your zoo guests will enjoy this colorful but deadly animal.

You must have either DD or CC to use this dinosaur.

87 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

Shuvuuia by Ghirin

By Guest

Shuvuuia was a member of the bird-like alvarezsaurid group. A distinguishing feature of this group was the short arm ending in a large claw. This might be an adaptation for digging for food.

Reference:

The Illustrated Ecyclopedia of Dinosaurs by Dougal Dixon. 2006

www.wikipedia.com

Created by Ghirin 2006

237 downloads

0 comments

Updated

-

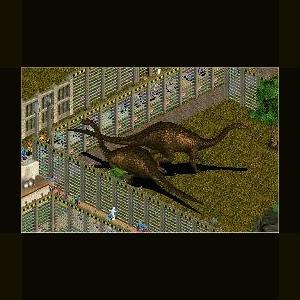

Yunnanosaurus by Moondawg

By Guest

Yunnanosaurus

Yunnanosaurus is a genus of prosauropod dinosaur from the Early to Middle Jurassic Period; a position in time that makes it one of the last prosauropods. It is closely related to Lufengosaurus. Known from two valid species, Yunnanosaurus ranged in size from 7 meters (23 feet) long and 2 m (7 ft) high to 13 m (42 ft) long in the largest species. It is known from over twenty skeletons, including two skulls, recovered from the Lufeng Formation of Yunnan, China.

Yang Zhongjian (aka C. C. Young) discovered the first Yunnanosaurus skeletons in the Lufeng Formation of Yunnan, China. The fossil find was composed over twenty incomplete skeletons, including two skulls, and were excavated by Tsun Yi Wang.

There were more than sixty spoon shaped teeth in the jaws of Yunnanosaurus, and were unique among prosauropods in that its teeth were self-sharpening because they "(wore) against each other as the animal fed." Scientists consider these teeth to be advanced compared to other prosauropods, as they share features with the sauropods.

However, scientists do not consider Yunnanosaurus to be especially close to the sauropods in phylogeny because the remaining portions of the animals body are distinctly prosauropod in design. This critical difference implies that the similarity in dentition between Yunnanosaurus and sauropods might be an example of convergent evolution.

type species, Y. huangi, was named by C. C. Young in 1942, and he erected the family Yunnanosauridae to contain it, though the family currently comprises only this genus. Young also named a second species, Y. robustus, in 1951, but this has since been included in the type species. The confusion in classification arose due to that the earliest specimens were of juveniles while the "Y. robustus" specimens represented fully grown adults.

In 2007, Lu and colleagues described another species of Yunnanosaurus, Y. youngi (named in honor of C. C. Young). In addition to various skeletal differences, at 13 meters (42 ft) long Y. youngi was significantly larger than Y. huangi (which reached only 7 meters (23 ft), and Y. youngi is found later in the fossil record, hailing from the Middle Jurassic.

179 downloads

0 comments

Updated